For decades, Hollywood has told stories that mostly reflect one kind of life: white, male, straight, and able-bodied. Even as audiences demand more variety, the screen still feels like a mirror held up to a narrow slice of society. The numbers don’t lie. In 2023, only 14% of lead actors in top-grossing U.S. films were from underrepresented racial or ethnic groups. Women made up just 36% of all speaking roles. And that’s before you even get to people with disabilities, LGBTQ+ identities, or Indigenous communities-groups that often disappear entirely from mainstream narratives.

Black and Brown Faces Still Rarely Lead

Black actors have made progress in supporting roles, but leading roles remain scarce. In 2024, only three out of the top 100 films featured a Black lead. That’s down from four in 2022. Latinx actors fared worse: just 5% of speaking roles went to them, despite making up nearly 20% of the U.S. population. And when they do appear, they’re often stuck in stereotypes: the gang member, the immigrant caregiver, the comedic sidekick. Films like Encanto and Minions: The Rise of Gru show what’s possible when Latinx culture is centered with dignity-but those are exceptions, not the rule.

Asian representation has improved since Crazy Rich Asians in 2018, but it’s still limited. Most Asian leads are still in comedies or martial arts films. In 2023, only one major studio film featured an East Asian woman as the protagonist. And South Asian, Southeast Asian, and Pacific Islander actors? Almost invisible. A 2025 UCLA study found that Pacific Islanders had the lowest representation of any major ethnic group in film-less than 0.1% of speaking roles.

Disabled Characters Are Still Played by Non-Disabled Actors

One in four adults in the U.S. lives with a disability. Yet in 2024, only 2.5% of characters in top films had disabilities-and 95% of those were portrayed by actors without disabilities. Think about it: a film about a veteran with PTSD casts a non-disabled actor in a wheelchair. A movie about a deaf musician hires a hearing actor to lip-sync to ASL. This isn’t just inaccurate-it’s harmful. It tells disabled people their stories aren’t worth telling unless filtered through someone who doesn’t live them.

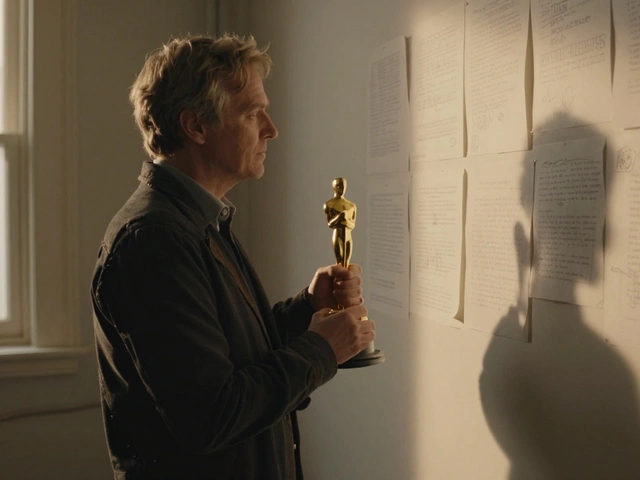

There are exceptions. CODA (2021) cast deaf actors in all deaf roles and won the Oscar for Best Picture. But since then, Hollywood has gone quiet. No major studio has followed up with a similar commitment. The same actors-Marlee Matlin, Troy Kotsur-are reused in every project, while new disabled talent stays locked out of auditions, casting calls, and development rooms.

LGBTQ+ Stories Are Still Told by Straight Filmmakers

LGBTQ+ characters appear more often now-but they’re still mostly sidekicks, tragic figures, or punchlines. A 2025 GLAAD report found that only 18% of LGBTQ+ characters in mainstream films were leads. Transgender characters? Just 3% of all LGBTQ+ representation, and nearly all were played by cisgender actors. The most common arc? Death. Over 40% of LGBTQ+ characters in 2023 films died by the end. That’s not storytelling. That’s trauma porn.

Queer stories written and directed by queer people-like Everything Everywhere All at Once or The Last of Us-break through. But they’re rare. Most studios still hand LGBTQ+ narratives to straight, cisgender writers who rely on clichés: the coming-out montage, the lonely gay best friend, the villain with a hidden queer identity. These aren’t authentic portrayals. They’re safety nets for audiences who aren’t ready to see real queer lives.

Indigenous Communities Are Erased or Romanticized

Native American, First Nations, and Indigenous Pacific Islander communities are treated like historical artifacts, not living cultures. In 2024, only two films featured Indigenous leads. One was a documentary. The other was a horror movie where the protagonist was a spirit guide. That’s not representation. That’s appropriation.

Even when Indigenous actors are cast, they’re often playing roles written for white people-cowboys, warriors, mystical shamans. There’s little room for modern Indigenous stories: a Navajo nurse in Phoenix, a Cree tech entrepreneur in Winnipeg, a Yup’ik teacher in Alaska. Studios claim they “can’t find” Indigenous talent, but the truth is they don’t look. They don’t partner with tribal film collectives. They don’t fund Indigenous-led production companies. The result? A generation of Indigenous storytellers are forced to make films on their own, with crowdfunding and cell phones, while Hollywood profits from their culture.

Women Over 40 Are Vanishing From the Screen

Women in film don’t just face gender bias-they face ageism too. A 2025 study from the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative found that women over 40 made up just 11% of speaking roles in top films. For women over 55? It dropped to 3%. Compare that to men: over 40% of male leads were over 40. The message is clear: women’s stories end at 40. Men get to be heroes, dads, and wise mentors. Women get to be the mom who dies in the first act or the quirky neighbor who delivers one-liners.

There are exceptions. Frances McDormand, Cate Blanchett, and Viola Davis keep working. But they’re outliers. Most women over 40 are pushed into supporting roles or disappear entirely. Even in indie films, scripts rarely center older women’s desires, ambitions, or conflicts. They’re not given love stories, career arcs, or redemption journeys. They’re background noise.

Why Does This Keep Happening?

It’s not just bias. It’s systems. Studios rely on “proven” formulas: white male leads = box office safety. Investors don’t want to risk money on “niche” stories. Casting directors recycle the same 200 actors. Writers’ rooms are still 80% white and male. And when someone tries to push change-like hiring a diverse director or casting a disabled actor-they’re told, “We tried that last year. It didn’t work.”

But here’s the truth: they didn’t try. They gave a token role to a marginalized actor, slapped a hashtag on the poster, and called it progress. Real inclusion means giving creative control to people from these communities. It means funding films from the ground up, not just casting a few people in existing projects. It means letting them write their own stories-without filters, without apologies, without needing to explain their humanity to white audiences.

Who’s Actually Making a Difference?

Change isn’t coming from the top. It’s coming from the margins. Organizations like the Black Film Center & Archive, Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund, and Indigenous Media Initiatives are training new talent, producing films, and demanding accountability. Streaming platforms like Netflix and Hulu have started greenlighting more diverse projects-but they’re still chasing trends, not building pipelines.

Independent filmmakers are the real engine. Films like The Inspection (2022), My Name Is Pauli Murray (2021), and Fire of Love (2022) were made with tiny budgets and zero studio backing. They found audiences because they told truths no studio wanted to touch. And now, those films are winning awards and getting distribution deals.

It’s not about quotas. It’s about access. Who gets to pitch? Who gets to direct? Who gets to say yes? Until those doors open, the same groups will stay invisible-not because they don’t exist, but because the system refuses to see them.

What Can You Do?

Watch films made by marginalized creators. Support indie distributors like Oscilloscope, Kino Lorber, or Grasshopper Film. Attend film festivals that spotlight underrepresented voices-like Sundance’s NEXT section, the LA Film Festival, or the Native American Film Festival. Don’t just stream the big studio releases. Seek out the ones that don’t have billboards or TikTok ads.

Call out lazy representation when you see it. If a film casts a non-disabled actor as a disabled character, say so. If a queer story ends in tragedy, point it out. Demand better. Streaming services listen when enough people complain.

And if you’re a creator? Start small. Make a short film. Write a script. Film it on your phone. Share it online. You don’t need a studio to tell a true story. You just need the courage to tell it.

Why don’t studios cast more actors from underrepresented groups?

It’s not that they can’t find them-it’s that they don’t look. Casting directors often rely on the same networks of actors, many of whom are white and from privileged backgrounds. Studios also believe-wrongly-that audiences won’t connect with leads who aren’t white men. But box office data shows otherwise: films like Black Panther, Everything Everywhere All at Once, and Minions: The Rise of Gru proved global audiences will turn out for diverse stories when they’re well-made.

Are streaming services helping or hurting diversity in film?

They’ve opened doors, but they’re still playing it safe. Platforms like Netflix and Apple TV+ have greenlit more diverse projects than traditional studios-but they often treat them as “content” rather than art. They prioritize quantity over quality, and they rarely give creators full control. Many diverse filmmakers end up losing creative rights when they sign with streamers. Real progress means giving marginalized creators ownership, not just access.

Why do disabled characters keep being played by non-disabled actors?

It’s a legacy of ableism in casting. Studios assume non-disabled actors can “play” disability better than disabled actors can play themselves. They believe it’s easier to train an actor to use a wheelchair than to find one who already uses one. But that’s not just false-it’s offensive. Disabled actors bring lived experience, authenticity, and nuance that no amount of research can replicate. Organizations like the Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund have been pushing for years to end this practice, and some studios are finally listening.

Is representation in film actually changing, or is it just performative?

Some change is real, but most of it is performative. Studios release one diverse film each year and call it a win. They put a rainbow flag on a poster or cast a Black actor in a supporting role and call it progress. But real inclusion means consistent, long-term investment: hiring diverse writers, directors, and producers; funding development programs; and creating pipelines for new talent. Right now, most diversity efforts are one-off campaigns-not systemic change.

What’s the difference between diversity and inclusion in film?

Diversity is who’s in front of the camera. Inclusion is who’s behind it. You can have a film with a diverse cast but a completely white, male, straight writing team. That’s not inclusion-that’s tokenism. True inclusion means giving marginalized people power: the power to write, direct, produce, and greenlight projects. Without that, representation is just decoration.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The next decade will decide whether film becomes a mirror for all of us-or just a window for a few. Right now, the system is rigged to protect the status quo. But audiences are tired of the same stories. They’re hungry for authenticity. They’re voting with their clicks, their tickets, and their voices.

The future of film doesn’t belong to the studios. It belongs to the people who tell stories no one asked for-and tell them anyway. To the Indigenous filmmaker in Oklahoma. To the deaf writer in Detroit. To the queer animator in Texas. To the disabled producer in Chicago. They’re not waiting for permission. They’re making the films. And if you watch them, support them, and amplify them, you’re not just watching movies. You’re helping rewrite the rules.

Comments(5)