Most screenwriters focus on plot. They build twists, raise stakes, and time their act breaks perfectly. But a movie that only has a good plot? It’s forgettable. The stories that stick with you-like theme in screenwriting-are the ones where the idea behind the story lingers long after the credits roll. Theme isn’t just a moral or a message you tack on at the end. It’s the heartbeat of the film. It’s what makes the hero’s journey matter. It’s why you care about the characters, even when they make terrible choices.

What Theme Actually Is (And What It Isn’t)

Theme isn’t "love conquers all" or "greed is bad." Those are slogans. Theme is the question your story asks, and the answer it finds through action. It’s not what you say. It’s what happens.

Think about The Godfather. The theme isn’t "family is important." That’s too simple. The theme is: How far will you go to protect your family, and at what cost to your soul? The story doesn’t preach. It shows Michael Corleone slowly becoming the very thing he swore to destroy-all to keep his family safe. The theme lives in his choices, not in a line of dialogue.

Same with Parasite. The theme isn’t "rich people are evil." It’s: Can class mobility ever be real when the system is rigged? The film doesn’t answer with a speech. It answers with a basement, a flood, and a knife.

Theme isn’t the lesson. It’s the wound the story tries to heal-or the wound it refuses to let heal.

Where Theme Comes From

Theme doesn’t come from a brainstorming session. It comes from what you care about. What keeps you up at night? What injustice makes your blood boil? What contradiction in human behavior fascinates you?

Screenwriter Charlie Kaufman didn’t sit down and say, "I want to write about identity." He was obsessed with the fear of losing himself-and that obsession became Being John Malkovich. The theme wasn’t added later. It was the reason he wrote the script.

When you start writing, ask yourself: What’s the one idea I can’t stop thinking about? That’s your theme. Not the plot. Not the characters. The idea.

Write it as a question. Not a statement. Questions drive stories. Statements preach.

- Is redemption possible after betrayal?

- Can you be free if you’re afraid of being alone?

- Does truth matter if no one believes it?

These aren’t themes you find. They’re themes you already carry. Your job is to build a world around them and see what happens.

How Theme Shapes Plot and Character

Plot is the skeleton. Theme is the nervous system. Every scene should pulse with it.

Take Mad Max: Fury Road. The plot is a car chase. The theme is: Can you fight for freedom without becoming the monster you hate? Furiosa doesn’t just want to escape. She wants to save the women. But to do it, she has to use violence, steal, and lie. Every action she takes tests that theme. The Immortan Joe isn’t just a villain-he’s the mirror. He controls through fear, just like she once did.

Characters aren’t just people with goals. They’re living arguments for or against the theme.

Look at Shawshank Redemption. Andy doesn’t just want to escape prison. He wants to prove that hope isn’t foolish. The theme is: Can hope survive in a place designed to kill it? Red says hope is dangerous. Andy lives it. Their conflict isn’t just personality-it’s philosophy.

When a character changes, they don’t just learn a lesson. They change their answer to the theme’s question.

How to Embed Theme Without Lecturing

Never have a character say: "The theme of this movie is..."

Instead, show it through:

- Repetition of imagery: In There Will Be Blood, oil wells, empty landscapes, and silence repeat-each one reinforcing the theme: Power consumes everything, even the soul.

- Contrasting characters: In Blade Runner 2049, K’s search for meaning is mirrored by the replicant children who never knew they were artificial. One seeks identity. The other never had a chance to question it.

- Symbolic actions: In Get Out, the hypnosis isn’t just a plot device. It’s the theme: Black bodies are treated as containers for white desires. The ritual isn’t horror-it’s logic.

- Setting as metaphor: In Her, the city is clean, quiet, and emotionally sterile. The theme-Can love exist when we’re more connected than ever yet feel more alone?-is written into the architecture.

Theme doesn’t need words. It needs patterns.

Testing Your Theme: The "So What?" Challenge

After you write a draft, ask yourself: Why does this matter?

If the answer is "It’s a cool story," you’re missing the point.

Try this test: Remove the theme. What’s left? If your story still works without it, you didn’t embed it-you just labeled it.

Take Little Miss Sunshine. The plot: a family drives to a beauty pageant. The theme: Success isn’t about winning-it’s about showing up as you are. If you took out the theme, you’d have a quirky road trip. But with the theme? You have a story about broken people choosing to be together, even when the world tells them they’re losers.

That’s the difference between a movie and a memory.

Common Mistakes Screenwriters Make

Most writers think theme is decoration. It’s not. Here’s what goes wrong:

- Theme as an afterthought: Writing the plot first, then slapping on a moral like "be yourself" at the end. That’s not theme. That’s a bumper sticker.

- Being too obvious: A character says, "I’ve learned that honesty is the best policy." No one believes that. And no one remembers it.

- Trying to please everyone: If your theme is "love is good and hate is bad," you’re not saying anything. It’s not a question-it’s a cliché.

- Ignoring contradiction: Real themes live in tension. If your hero is always right, the theme has no weight. The best stories make you uncomfortable. They force you to sit with the ambiguity.

Theme isn’t about being right. It’s about being honest.

Theme in Practice: A Real Example

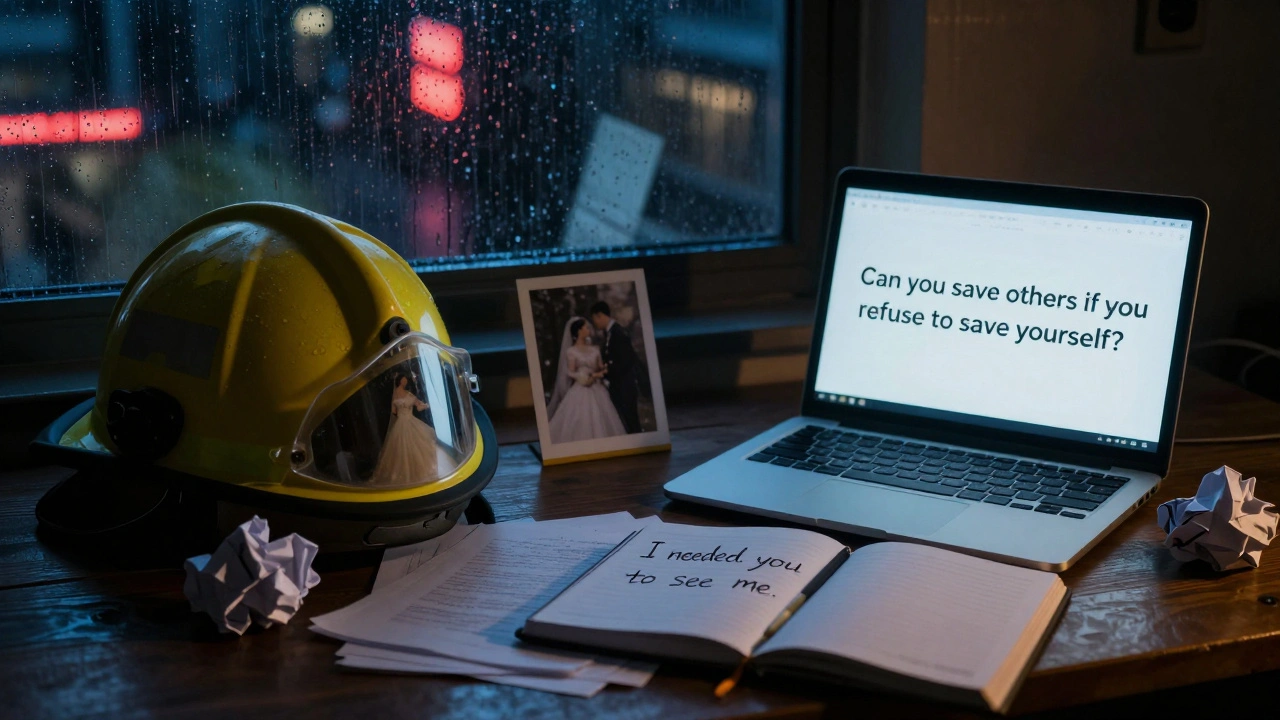

Let’s say you’re writing a script about a firefighter who saves people but can’t save his own marriage.

Plot idea: He’s called to a burning building. He rescues a family. But when he gets home, his wife has left.

That’s a scene. Not a story.

Now ask: What’s the question? Can you save others if you refuse to save yourself?

Now rebuild the story around that.

- He’s good at his job because he’s good at shutting down emotion.

- His wife tried to reach him. He kept saying he was too busy.

- He saves a child in a fire-but the child’s mother dies. He breaks down for the first time.

- He finds his wife’s journal. She wrote: "I didn’t need you to fix me. I needed you to see me."

- Final scene: He doesn’t go back to work. He walks into a community center and starts teaching kids fire safety. Not to save lives. To be present.

That’s theme. It’s not stated. It’s felt.

Final Thought: Theme Is the Reason Your Story Exists

Every great film starts with a question. Not a logline. Not a character. A question that haunts the writer.

That’s your theme.

Don’t write a story because you think it’ll sell. Write it because you can’t not write it. Because the idea keeps whispering to you.

When you do that, the plot will follow. The characters will rise. The audience will feel it-even if they can’t name it.

That’s the power of theme in screenwriting.

What’s the difference between theme and plot in screenwriting?

Plot is what happens. Theme is why it matters. Plot is the car chase in Mad Max: Fury Road. Theme is the question: Can you fight for freedom without becoming the monster you hate? The plot moves the story forward. The theme gives it meaning.

Can a movie have more than one theme?

Yes, but they need to connect. The Dark Knight explores chaos vs. order, but also sacrifice and moral compromise. These aren’t separate themes-they’re layers of the same question: How far will you go to protect what you believe in? Multiple themes work when they deepen, not distract.

How do I find my theme if I’m stuck?

Look at your favorite scenes. What emotion do they leave you with? What moment made you pause? That’s your theme. Write it as a question. "Why did that hurt?" is often the key. Don’t force it. Let it emerge from what you care about.

Do I need to state the theme in the script?

Never. Theme is shown, not told. If a character says, "This movie is about redemption," you’ve failed. Let the audience discover it through actions, choices, and consequences. The best themes are felt, not explained.

Can theme change during rewriting?

Absolutely. Many writers don’t know their theme until they’ve written 50 pages. That’s normal. When you see a pattern-repeated images, character arcs, emotional beats-that’s your theme emerging. Let it evolve. Don’t force it to match your original idea.

Comments(5)