Ever watched a movie and thought, That music is perfect-only to find out the score you loved wasn’t the final one? You’re not imagining it. That’s temp love in action.

Temp tracks-temporary music cues added during editing-are everywhere in modern film. They’re not just placeholders. They’re emotional anchors. Directors, editors, and even studios fall for them hard. And once they do, the real challenge begins: finding a composer who can match or beat that feeling without copying it.

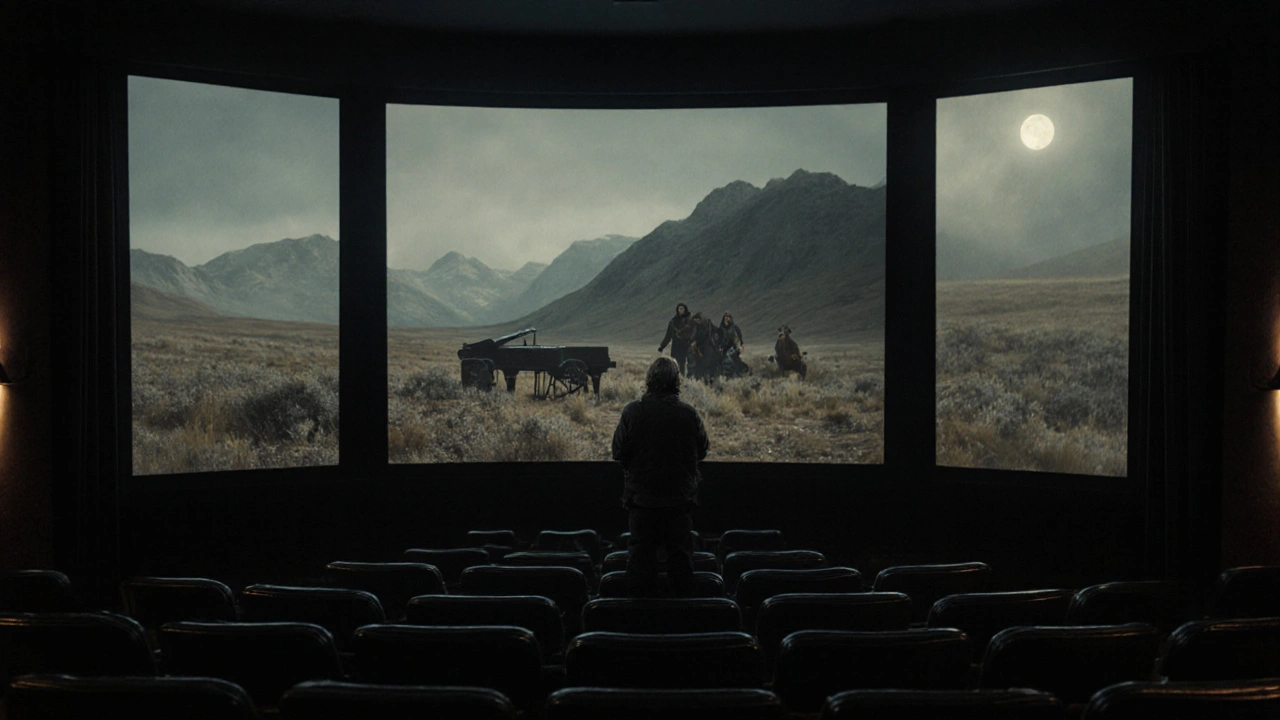

It starts in the cutting room. A scene feels flat. The editor grabs a piece of Hans Zimmer’s Inception score, drops it under the chase sequence, and suddenly-boom-the tension clicks. The director watches it three times in a row. They nod. They say, That’s the vibe. That’s the sound.

But here’s the problem: that temp track was written for a completely different movie. It’s not built for your scene. It doesn’t know your characters. It doesn’t care about your story. Yet now, it’s the ghost haunting every draft of the final score.

The Psychology of Temp Tracks

Temp tracks don’t just guide the music-they shape expectations. A 2019 study by the University of Southern California’s Cinematic Arts department found that 87% of directors showed temp tracks to composers before recording a single note. And in 63% of those cases, the composer was asked to match the temp, not just be inspired by it.

It’s not laziness. It’s efficiency. A temp track communicates emotion faster than words. Saying “make it feel like the opening of Interstellar” is easier than describing a rising minor ninth chord over a timpani roll with a low cello drone. But that shortcut comes at a cost.

Composers often feel trapped. They’re handed a temp track and told, “This is what we want.” But what they’re really being asked for is a forgery. A copy that feels original. A sound that’s already been heard-and already belongs to someone else.

When Temp Tracks Win

Some temp tracks never leave the film. They become the final score.

Think of Gladiator. The temp track used during editing was a mix of classical pieces and modern orchestral works. When Hans Zimmer and Lisa Gerrard were brought on, they were told to match the emotional weight of that temp. The result? The final score sounds nothing like the temp-but it carries the same soul. That’s the holy grail: matching the feeling, not the notes.

But sometimes, the temp wins outright. Iron Man (2008) used a temp track featuring the song “Back in Black” by AC/DC. The studio loved it so much they asked the composer to write something that felt like it. The final score? No AC/DC. But the rhythm, the swagger, the electric energy? All borrowed from the temp. The temp didn’t just influence the score-it defined it.

Even Star Wars had temp tracks. George Lucas used classical pieces from Richard Strauss and Sergei Prokofiev during early cuts. John Williams didn’t copy them-he absorbed them. He didn’t recreate the temp. He reimagined it. That’s the difference between copying and channeling.

The Composer’s Dilemma

Composers aren’t just writing music. They’re solving a puzzle with emotional constraints.

Take a film like Arrival. The temp track used haunting, slow-moving ambient pads. The director wanted something that felt alien, slow, and deeply emotional. The composer, Jóhann Jóhannsson, didn’t use strings or percussion. He used modified cello recordings, reversed voices, and sub-bass tones. He avoided melody entirely. The result? A score that felt completely new-but still matched the temp’s emotional weight.

But not every composer can do that. Many are pressured to replicate the temp note-for-note. One composer told me, “I spent six weeks rewriting a cue because the director kept saying, ‘It’s not quite like the temp.’ But the temp was a piece by Thomas Newman. I couldn’t play like him. I’m not him.”

That’s the trap. Temp tracks create a standard that’s impossible to meet unless you’re the original artist. And yet, studios expect it.

How Temp Tracks Change the Final Sound

Temp tracks don’t just influence melody-they change structure.

Let’s say a scene is 90 seconds long. The temp track builds slowly over 60 seconds, peaks at 75, and fades out at 88. The director cuts the scene to match that timing. The composer then has to write a score that fits that exact rhythm-even if the scene’s pacing doesn’t naturally demand it.

That’s how you get scores that feel mechanical. Not because the music is bad-but because it was forced into a shape that wasn’t organic to the film.

Compare that to The Revenant. The temp track used ambient drones and natural sounds. But the director, Alejandro González Iñárritu, didn’t want music that matched the temp. He wanted music that felt like the wilderness. The composer, Ryuichi Sakamoto, used only piano, wind, and water. He ignored the temp’s structure entirely. The result? A score that feels like it grew from the film, not imposed on it.

Temp tracks can be useful. But they can also blind you to better options.

When Temp Tracks Hurt the Film

Not all temp love ends well.

One indie film I worked on used a temp track from Blade Runner 2049. The temp had a slow, pulsing synth bass and distant vocal echoes. The composer spent months trying to recreate it. When the final score was delivered, the director said, “It’s good… but it’s not that.” He didn’t realize the temp was a masterpiece by a world-class composer. The film’s budget couldn’t support that level of sound design. The result? A score that felt cheap by comparison.

Worse, the temp track made the director believe the film needed more tension than it did. The final cut became slower, heavier, more oppressive-all because the temp made every scene feel like it needed a dramatic swell.

Temp tracks can make directors think their film is more epic than it is. They can make comedies feel like thrillers. They can turn quiet moments into emotional earthquakes.

One editor told me, “I’ve seen films where the temp track was so powerful, the director refused to cut a single frame-even if the scene was dragging-because the music made it feel perfect.” That’s dangerous. Music shouldn’t fix pacing. It should enhance it.

How to Break Free from Temp Love

So how do you avoid falling into the temp trap?

- Use temp tracks early, then let them go. Add them during the first cut to test emotion. But by the third cut, remove them. Watch the scene silent. Does it still work?

- Ask for emotion, not sound. Instead of saying, “Make it like this,” say, “I want the audience to feel like they’re holding their breath.”

- Let the composer hear the scene without the temp. The first time they see the scene, it should be silent. That’s when their creativity is purest.

- Use multiple temp tracks. Don’t just use one. Show three different styles. That gives the composer room to explore, not just replicate.

- Know your budget. If your temp track is by Hans Zimmer, your composer can’t match it. Adjust expectations.

Temp tracks are tools. Not masters.

The Legacy of Temp Love

Temp love isn’t going away. It’s too useful. Too fast. Too emotionally convincing.

But the best films don’t just use temp tracks-they transcend them. They take the feeling, not the formula. They find new ways to say what the temp said, but in a voice that belongs to the film alone.

When done right, temp love becomes a bridge-not a cage. It helps filmmakers find their way to a sound they didn’t know they needed. And when the final score arrives, it doesn’t sound like the temp. It sounds like the movie.

That’s the magic. Not in copying. But in becoming.

What is a temp track in film?

A temp track is temporary music added during film editing to help guide the emotional tone of a scene. It’s usually a piece of existing music from another film or album, used until the original score is composed. It’s not meant to be final-but often ends up shaping it.

Why do directors use temp tracks?

Directors use temp tracks because they communicate emotion faster than words. A temp track helps editors time cuts, test pacing, and show composers exactly what kind of feeling they’re going for. It’s a shortcut to shared understanding.

Can a temp track become the final score?

Yes, but rarely. Sometimes studios keep the temp track if it’s already licensed and fits perfectly-like in Iron Man, where the AC/DC vibe was so strong they kept the energy even without the original song. More often, the temp inspires the final score, but the composer writes something original.

Do composers hate temp tracks?

Not all of them. Many see temp tracks as helpful starting points. But many also feel frustrated when they’re asked to copy someone else’s work instead of creating something new. The best composers use temp as inspiration, not a blueprint.

How do temp tracks affect film pacing?

Temp tracks often dictate scene length and rhythm. If the temp builds over 70 seconds, editors will cut the scene to match-even if the visuals don’t naturally support that timing. This can make scenes feel forced or unnatural when the final score doesn’t match the same structure.

Comments(5)