Most people think big studios own the box office. They spend millions on ads, lock down theaters, and roll out movies with celebrity trailers and TikTok campaigns. But over the last 15 years, a quiet revolution has happened: independent films, funded by filmmakers themselves and distributed without any studio help, have walked right past Hollywood giants and made more money. Not just a little more. Some made over ten times their budget in theaters alone.

How a $50,000 Movie Made $10 Million

In 2011, a couple from Texas spent their life savings-$50,000-to make a horror movie called The Blair Witch Project. They shot it on a camcorder, used non-professional actors, and didn’t even have a proper script. No studio wanted it. So they self-distributed. They rented a few theaters in Austin and Salt Lake City, ran local radio ads, and let word of mouth do the rest. Within three months, it had grossed over $140 million worldwide. It wasn’t just a hit. It was the highest-grossing indie film of all time at that point, and it still holds the record for best return on investment in cinema history.

That movie didn’t have a marketing team. It didn’t have a Netflix deal. It had one thing: a story so strange, so real, that people couldn’t stop talking about it. And when you let audiences spread the word, you don’t need a $20 million ad buy.

The Rise of the DIY Distributor

Before streaming, before social media, before YouTube, indie filmmakers had one choice: beg studios for a release. Most got ignored. A few got a limited run in five cities and vanished. But around 2005, something changed. Digital cameras got cheaper. Editing software became free. And platforms like Vimeo and YouTube let filmmakers show their work directly to viewers.

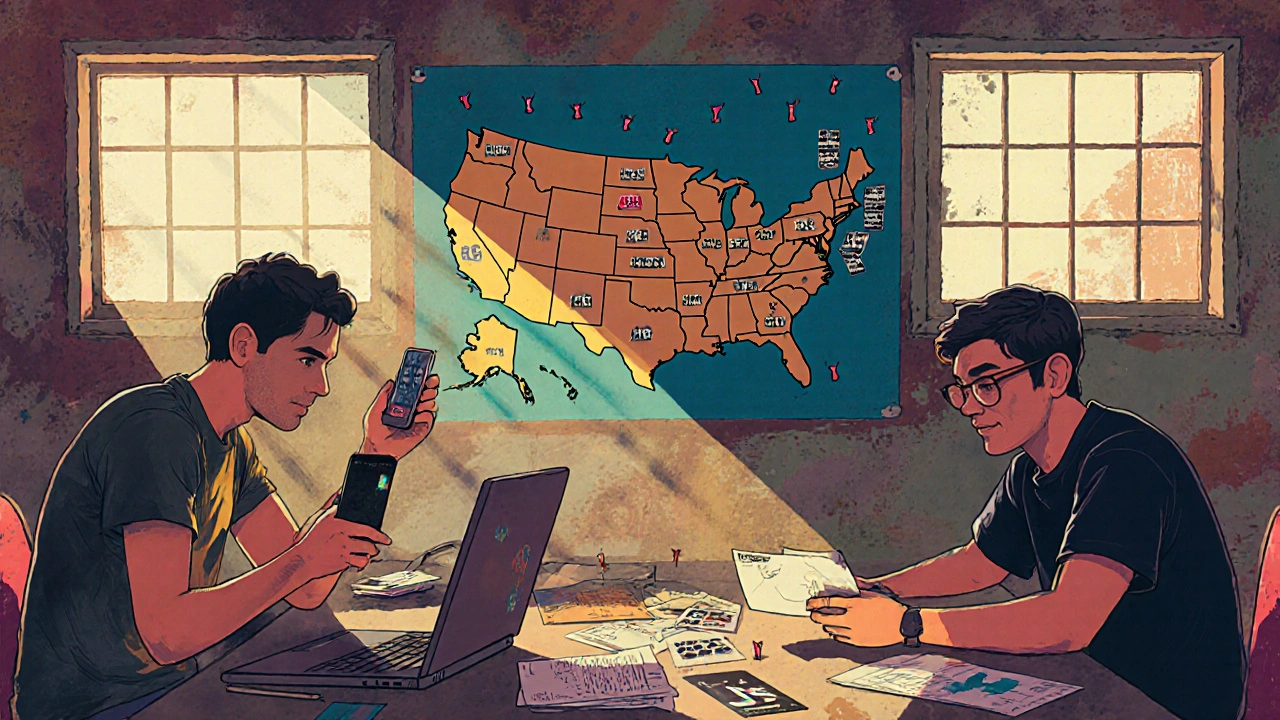

That’s when self-distribution became real. Filmmakers stopped waiting for permission. They started booking theaters themselves. They called local radio stations. They partnered with community centers and film clubs. They ran Facebook ads for $50. They mailed postcards to people who liked similar movies.

Take Little Miss Sunshine. Made for $8 million, it was picked up by Fox Searchlight after Sundance-but that wasn’t the full story. Before the studio even bought it, the filmmakers had already booked 20 theaters in California and Arizona. They sold tickets at the door. They held Q&As with the cast. They turned the film into a movement. When Fox finally released it nationwide, it opened at #1 in limited release and went on to earn $100 million globally. The studio didn’t make it a hit. The filmmakers did.

What Self-Distribution Really Means

Self-distribution isn’t just putting your movie on YouTube. It’s a full-time job. It’s understanding your audience better than any focus group ever could. It’s knowing that your film isn’t for everyone-it’s for a specific group of people who will show up, tell their friends, and come back for the second screening.

Take Paranormal Activity. Made for $15,000, it was screened in a handful of theaters in 2007. The filmmakers tracked who showed up. They noticed that young women in their early 20s were the most likely to bring friends. So they targeted college campuses. They partnered with dorm councils. They offered free popcorn if you brought three people. They didn’t advertise the plot. They advertised the experience: "You won’t believe what happens at the end. Bring someone who screams easily."

By the time Paramount picked it up, the film had already made $2 million in test screenings. When it hit wide release in 2009, it opened at #1 and earned over $193 million. The studio just scaled what the filmmakers had already proven.

Why Studios Can’t Copy This

Big studios are built to minimize risk. They want to spend $100 million and make $500 million. They need broad appeal. They need stars. They need global marketing. That’s why they make sequels, reboots, and superhero movies. They don’t gamble on weird, quiet, or uncomfortable stories.

But indie filmmakers don’t have that pressure. Their only goal is to break even. If they make $100,000 on a $30,000 film, they’re billionaires. That freedom lets them take risks studios won’t touch.

Consider Tangerine. Shot entirely on an iPhone 5s in 2015. No lighting crew. No permits. Two transgender sex workers as leads. No studio would touch it. But the director, Sean Baker, self-distributed it through a mix of film festivals, Instagram ads targeting LGBTQ+ communities, and partnerships with local theaters in New York and Los Angeles. It earned $4.3 million. That’s 140 times its budget. And it didn’t need a trailer with a pop song.

The New Rules of Indie Success

Here’s what works now:

- Know your audience-not demographics, but psychographics. Who are they? Where do they hang out? What do they care about? Paranormal Activity didn’t target horror fans. It targeted college kids who wanted to scream together.

- Start small, but start local-book one theater in your city. Host a premiere. Invite the press. Get local news to cover it. People show up for events, not just movies.

- Use free tools-Instagram, TikTok, email lists, YouTube shorts. No budget? Use your phone. Film a 15-second clip of your lead actor talking about why the story matters. Post it. Repeat.

- Build a community, not a campaign-respond to every comment. Thank every person who shares. Make your audience feel like they’re part of the movie’s journey.

- Track everything-how many tickets sold in week one? Which city had the highest turnout? Which ad got the most clicks? Use Google Analytics, Box Office Mojo, or even a simple spreadsheet. Data beats guesswork.

Recent Wins That Prove the Model Still Works

In 2023, The Last Days of American Crime was released by a small team in New Orleans. Budget: $1.2 million. No studio. No stars. They booked 120 theaters across the South and Midwest. They partnered with local churches, bookstores, and music venues to host screenings. They didn’t advertise the plot. They advertised the vibe: "A movie about giving up everything to live free."

It opened at #12 nationwide. By week three, it had grossed $8.7 million. That’s 7 times its budget. And it didn’t have a single TV commercial.

Then there’s Everything Everywhere All at Once. Made for $25 million, it was released by A24-but the team behind it had spent years self-distributing shorts and documentaries. They knew how to build buzz. They didn’t rely on trailers. They released memes. They turned Michelle Yeoh’s character into a cultural icon. They didn’t wait for the studio to act. They acted first.

What Happens When You Don’t Self-Distribute

Many indie films never make it past film festivals. They get picked up by a distributor who promises a wide release… then quietly puts the film on VOD after two weeks in three theaters. The filmmaker gets a check for $5,000 and disappears.

That’s the trap. Waiting for someone else to validate your work. The truth? No studio is going to care about your movie unless audiences already do. And audiences only care if you show them why it matters-before they ever see the trailer.

Self-distribution isn’t about being anti-studio. It’s about being pro-audience. It’s about realizing that your film doesn’t need a billion-dollar budget. It needs one person to say, "You have to see this." And then another. And another.

It’s Not About Money. It’s About Control.

The real win isn’t the box office number. It’s knowing you made something real. That you didn’t compromise. That you didn’t wait for permission. That you built something from nothing-and kept it yours.

When My Neighbor Totoro was first released in Japan in 1988, it barely made back its budget. But the director, Hayao Miyazaki, didn’t care. He knew it would find its people. And it did. Over 30 years later, it’s one of the most beloved films in the world. No studio pushed it. Fans did.

That’s the power of self-distribution. You don’t need a studio to make a classic. You just need an audience that believes in you.

Can a low-budget film really compete with Hollywood blockbusters?

Yes, if it connects deeply with a specific audience. Films like The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity made hundreds of millions by targeting niche groups and letting word of mouth spread. They didn’t need bigger budgets-they needed better storytelling and smarter audience engagement.

What’s the difference between self-distribution and traditional indie distribution?

Traditional indie distribution means selling your film to a company like A24 or IFC Films. They handle marketing and theater bookings, but take a large cut and control the timeline. Self-distribution means you handle everything yourself-booking theaters, running ads, managing press-but you keep nearly all the revenue and full creative control.

Do I need a big social media following to self-distribute?

No. Many successful self-distributed films started with zero followers. What matters is knowing who your audience is and reaching them where they already are-local film clubs, Reddit threads, Facebook groups, community centers. One viral TikTok video from a real viewer can do more than a $10,000 ad campaign.

How do I book theaters without a distributor?

Start with independent theaters. Call them directly. Offer to split ticket revenue 50/50. Bring your own promotional materials. Offer a Q&A with the cast. Many theaters are eager for fresh content-they’re tired of reruns. Film festivals like Sundance or SXSW also have resources for filmmakers looking to book screenings.

Is self-distribution worth the effort?

If your goal is to make money quickly or get rich, maybe not. But if you want to make a film that matters, reach the right people, and keep control of your work, then yes. Many filmmakers who self-distribute earn more per viewer than those who sign with studios. And they build lasting careers by owning their audience.

Comments(10)