Back in 2019, a new movie opening in theaters meant a 90-day wait before you could rent it at home. Today, that same movie might hit premium video-on-demand (PVOD) just 17 days after its theater debut. The old rules don’t apply anymore. The way movies earn money has completely changed-and it’s not just about streaming. It’s about timing, money, and who gets paid when.

The Old System: Theatrical First, Always

For decades, the movie business ran on a simple rhythm: theaters first, then home video, then TV, then streaming. Studios counted on theaters to make the bulk of their money. A big movie like Avengers: Endgame made over $2.8 billion worldwide, and nearly 70% of that came from ticket sales. Theaters took about half, but studios still walked away with hundreds of millions. That money paid for the next movie.

After theaters, DVDs and Blu-rays came next. People bought them, rented them, even traded them. In 2005, home video sales brought in $18 billion in the U.S. alone. Then came digital rentals. By 2015, you could rent a new release for $20 on iTunes. That was still profitable. But the real money was always in the theater window. It was the engine.

The Disruption: Pandemic Pressure and the Collapse of the Window

Then came 2020. Theaters closed. Studios panicked. Universal made a bold move: they released Trolls World Tour on PVOD for $19.99 the same day it hit theaters. It made $100 million in three weeks. That’s more than most movies made in theaters during the pandemic. Suddenly, studios realized: maybe people would pay for movies at home if they had to.

Disney followed with Hamilton on Disney+, Black Widow on Premier Access. Warner Bros. put all 2021 films on HBO Max the same day as theaters. The old 90-day window? Gone. The industry had no choice. But what happened after the theaters reopened?

The New Math: PVOD as a Profit Engine

Today, PVOD isn’t just a backup plan-it’s a core revenue stream. Studios now plan for it from day one. A movie like The Little Mermaid (2023) made $56 million in theaters. But it made $42 million in PVOD rentals in its first month. That’s not a bonus. That’s half the total revenue.

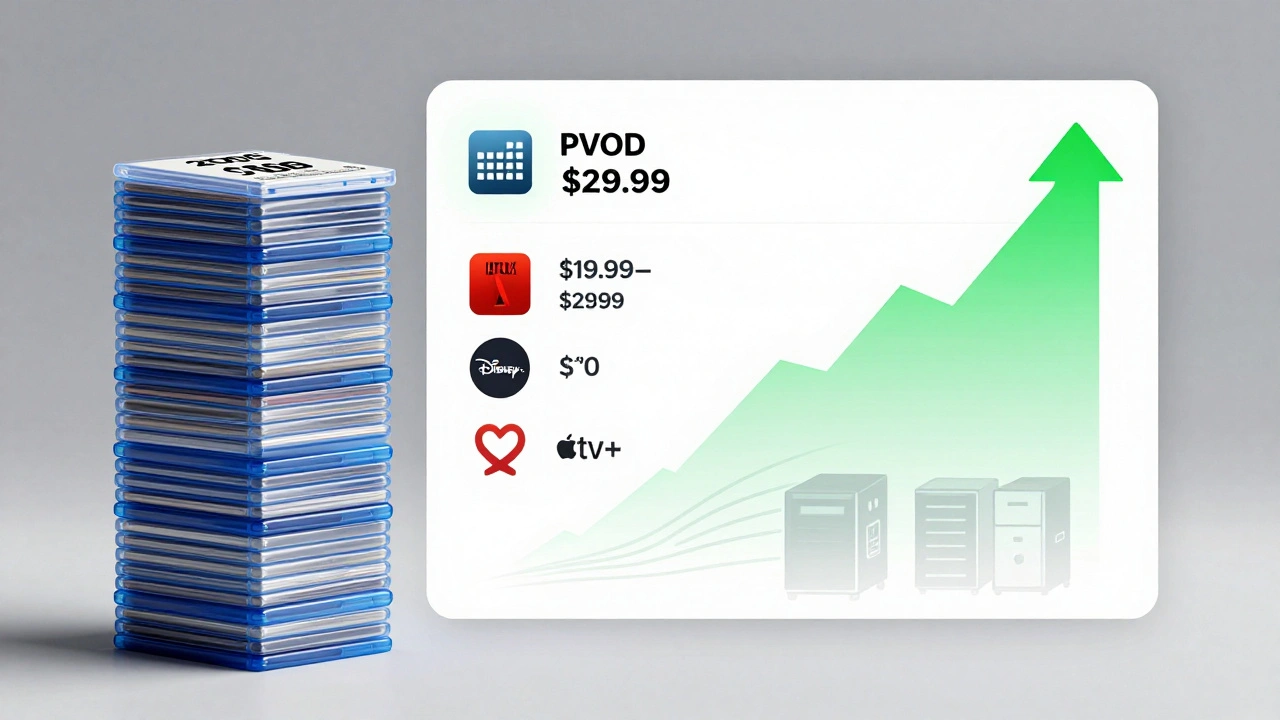

Here’s how it works: PVOD lets you rent a new movie for $19.99 to $29.99 for 48 hours. Studios keep 70-85% of that revenue, compared to 50% in theaters. That means if 1 million people rent a $24.99 movie, the studio makes $16.7 million. That’s more than most films made in theaters in 2015.

And the window? It’s down to 17-45 days. Some studios, like Sony, now use a 30-day theatrical window before PVOD. Others, like Paramount, test 17-day windows for mid-budget films. The goal isn’t to replace theaters-it’s to capture money that would’ve been lost if people waited for streaming.

SVOD: The Long Game

Then there’s SVOD-subscription services like Netflix, Hulu, and Apple TV+. This is where movies go after PVOD. But the timing? It’s not fixed anymore. In 2018, a movie might land on Netflix 9-12 months after theaters. Today, it’s 4-8 months. Some films go straight to SVOD if they’re not expected to do well in theaters.

Here’s the catch: SVOD deals are often flat fees. Netflix paid $25 million for the streaming rights to Army of the Dead. That’s a lot-but it’s not a percentage of revenue. If the movie had made $100 million in PVOD, the studio would’ve kept $70 million. The flat fee is safer, but it’s also lower risk for the streamer.

For studios, SVOD is a way to recoup costs and build library value. A movie like Knives Out made $311 million total-$262 million from PVOD and SVOD combined. Theaters only brought in $49 million. That’s the new reality: theaters are the trailer. SVOD is the main event.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

Movie theaters are struggling. AMC, Regal, and Cinemark saw attendance drop 40% from 2019 to 2024. They’re still the place for blockbusters like Mad Max: Fury Road or Oppenheimer. But for mid-budget films-comedies, thrillers, dramas-theaters are a gamble. Studios now use box office numbers as a marketing tool, not a profit driver.

Streaming platforms win by locking in subscribers. A hit movie on Netflix keeps people paying. Disney+ uses Marvel and Pixar films to drive sign-ups. Apple TV+ uses prestige films to build brand value. They don’t need to make money on every movie. They need you to stay subscribed.

For audiences? It’s never been easier-or cheaper-to watch new movies. But it’s also harder to know when to watch. Do you wait for the $20 rental? Pay $12 a month for a streamer? Or go to the theater for the experience? Each choice has a different cost-and a different reward.

The Future: Hybrid Windows and Dynamic Pricing

By 2026, we’ll see even more flexibility. Studios are testing dynamic release windows. If a movie makes $5 million in its first weekend, it goes to PVOD in 17 days. If it makes $1 million? It goes to SVOD in 30 days. Algorithms track real-time data: ticket sales, social buzz, rental demand, even theater occupancy rates.

Some experts predict the end of fixed windows. Instead, movies will move between channels based on performance. A film might start in theaters, shift to PVOD if it’s underperforming, then land on SVOD after 60 days. Or skip theaters entirely and go straight to PVOD if the marketing is strong enough.

Independent films are already doing this. A $2 million indie might skip theaters and launch on PVOD with a $14.99 price point. If it gets 200,000 rentals, that’s $2.8 million in revenue. No theater cuts. No distributor fees. Just pure profit.

What This Means for You

If you’re a movie fan, you’re getting more choices-but you’re also paying more across different platforms. You might pay $20 to rent a new release, $12 a month for a streamer, and $15 for a theater ticket. The total cost to watch everything can add up.

If you’re a studio executive, the game is about speed and data. You need to know when to pull a movie from theaters, when to push it to PVOD, and when to sell it to a streamer. The old model of waiting 12 months for SVOD is dead.

If you’re an investor? Look at the revenue mix. A studio that gets 60% of its revenue from PVOD and SVOD is more stable than one that relies on theaters. Theaters are a brand builder. PVOD and SVOD are profit engines.

Final Thought: The Window Isn’t Closed-It’s Just Different

The movie business didn’t die when theaters closed. It evolved. Theatrical releases still matter-they create buzz, build franchises, and give audiences a shared experience. But they’re no longer the main source of income. PVOD and SVOD are now the backbone of movie economics.

The next time you see a new movie, ask yourself: Is this worth $20 to watch tonight? Or should I wait a month for it on my subscription? That decision isn’t just about convenience. It’s shaping the future of Hollywood.

What is PVOD and how does it differ from SVOD?

PVOD stands for Premium Video-on-Demand. It lets you rent a newly released movie for $19.99-$29.99 for 48 hours, usually within weeks of its theater debut. SVOD, or Subscription Video-on-Demand, is what you get with Netflix or Hulu-you pay a monthly fee and can watch a library of films anytime. PVOD is pay-per-view. SVOD is pay-per-month.

Why did studios shorten the theatrical window?

Theaters closed during the pandemic, and studios realized audiences were willing to pay for new movies at home. PVOD proved more profitable than expected. Studios kept the shorter windows because they could make more money faster. A 30-day window with PVOD can generate more revenue than a 90-day window with just theaters.

Do theaters still make money from movies?

Yes-but only for big blockbusters. Films like Barbie or The Marvels still draw crowds. For mid-budget films, theaters are often a loss leader. Studios use them to build hype, not profit. The real money now comes from PVOD and SVOD deals.

How do studios decide when to move a movie to SVOD?

It depends on performance. If a movie earns $10 million or more in PVOD within 60 days, it stays in that window longer. If it earns less than $5 million, studios often sell it to a streamer sooner. Some use data tools that predict SVOD value based on social trends, rental demand, and audience demographics.

Are movie theaters going out of business?

Not all of them. Large chains like AMC still operate thousands of screens. But attendance is down 40% since 2019. Many smaller theaters have closed. Theaters that survive focus on premium experiences-IMAX, recliners, food service, and exclusive events. They’re no longer the primary revenue source-they’re brand ambassadors.

Comments(10)