Most people think becoming a film director means going to film school, landing an assistant job on a big set, and working your way up for ten years. That’s not the whole story. In 2025, more first-time directors launched feature films with under $50,000 than ever before. You don’t need Hollywood connections. You don’t need a big studio. You just need to know what to do next.

Start with a story you can actually make

Too many first-time directors pick scripts that require 50 locations, 30 actors, and a helicopter shot. Then they run out of money by day three. The best debut films are simple. They take place in one house. They have three characters. They rely on emotion, not spectacle.

Look at Whiplash. It was made for $3.3 million. Most of it takes place in a practice room. Or Tangerine, shot entirely on an iPhone. These films worked because the directors didn’t try to make a blockbuster. They made a story they could shoot with what they had.

Ask yourself: Can I shoot this in my neighborhood? Can I cast it with friends or local actors? Can I light it with natural light or a single LED panel? If the answer is no, rewrite it. Your first film isn’t a test of your ambition-it’s a test of your resourcefulness.

Build a team, not a resume

You don’t need to hire a director of photography with 15 years of experience. You need someone who shows up early, listens, and cares about the same thing you do: the story.

Find your crew the same way you’d find your best friends: through shared passion. Go to local film screenings. Join online groups for indie filmmakers in your state. Offer to work for free on someone else’s short film in exchange for them helping you. People will help you if you’re humble and clear about what you need.

Your cinematographer might be a college student with a used Canon C70. Your sound recordist could be a barista who edits podcasts on the side. That’s fine. What matters is that they understand your vision. Test them with a short scene. See how they respond to feedback. If they’re stubborn or disorganized, move on. Trust matters more than credits.

Plan like a strategist, not a perfectionist

Planning isn’t about storyboards for every shot. It’s about knowing what you can’t afford to lose.

Break your script into scenes. For each one, ask:

- What’s the emotional goal?

- What’s the minimum equipment needed?

- What’s the backup plan if it rains?

- What’s the one shot I absolutely must get?

Then build your schedule around those answers. Shoot all the interior scenes in one block. Film the most expensive scene on the day with the best weather forecast. Always have a two-day buffer. No film ever went over schedule without chaos.

Use free tools like StudioBinder or even Google Sheets. Don’t overcomplicate it. Your goal isn’t to make a perfect schedule. It’s to avoid running out of time before you finish the story.

Shoot fast. Edit faster.

Most first-time directors spend months shooting and then panic when they get to editing. Don’t wait. Start editing while you’re still filming.

Transfer your footage every night. Watch it. Cut rough sequences. See what works. You’ll spot problems early-bad performances, mismatched lighting, awkward dialogue-before it’s too late to fix them.

Use DaVinci Resolve. It’s free. It’s powerful. It handles 4K footage without breaking a sweat. You don’t need Final Cut or Premiere Pro. You need consistency. Shoot in LOG or flat profiles if you can. It gives you room to fix color later.

And here’s the truth: your first cut will suck. Everyone’s does. Don’t get discouraged. Edit for rhythm, not perfection. Cut out every second that doesn’t move the story forward. If a scene doesn’t change how the character feels, cut it.

Submit to festivals-early and often

Don’t wait for a distributor to find you. Festivals are your launchpad. And they’re not just for big cities.

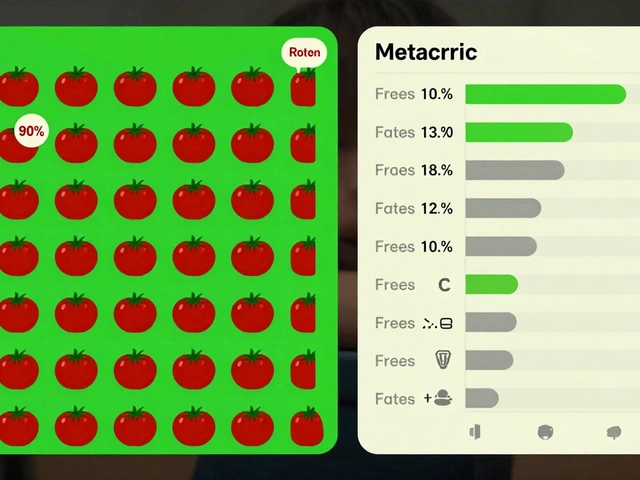

Start with regional festivals. Slamdance, South by Southwest, and Sundance get all the attention, but smaller ones like the Nashville Film Festival, the Big Island Film Festival, or the Mammoth Film Festival are hungry for fresh voices. They’re easier to get into. And they have real audiences.

Submit early. Pay the fee. Fill out the form honestly. Don’t lie about budget or cast. Festival programmers can tell. They’ve seen 10,000 films. They want authenticity, not hype.

Even if you don’t win, getting accepted means you’re now a "festival director." That’s a credential. It opens doors. It gets you noticed by producers. It makes people take you seriously.

Learn from rejection. Don’t let it stop you.

Rejection isn’t failure. It’s feedback.

If your film gets rejected from five festivals, ask why. Was the sound muddy? Did the pacing drag? Was the ending confusing? Don’t guess. Reach out. Most programmers will reply if you ask politely.

Use that feedback. Reshoot a scene. Redo the sound mix. Tighten the edit. Then submit again. One director I know submitted his first film to 27 festivals over two years. It got rejected 22 times. The 23rd time, it won Best New Director at a small festival. That led to a distribution deal.

Every great director was rejected first. It’s part of the job.

Build your next project while you’re still finishing the first

Don’t wait until your first film is done to think about the next one. Start now.

Write down three ideas. Talk to people you met on your first shoot. Ask them what they’d like to see next. Keep a notebook of moments you saw that felt cinematic-a street musician playing in the rain, a woman crying in a diner, a kid staring at a broken toy.

Your second film will be easier. You’ll know how to cast. You’ll know how to schedule. You’ll know what equipment to rent and what to avoid. You’ll have a network. You’ll have proof you can finish something.

That’s the real secret: directing isn’t about talent. It’s about showing up again and again.

What comes after your first film?

After your debut, you have three paths:

- Make a bigger film with the same team and more money.

- Work as a director for hire on commercials or web series to build credits.

- Teach, mentor, or run workshops to stay connected to the community.

None of these are "better" than the others. They’re just different. Some directors go straight to Netflix. Others spend years making shorts and documentaries before their first feature. There’s no timeline.

What matters is that you keep making films. Not because you want fame. But because you can’t stop telling stories.

That’s what makes a director.

Do I need film school to become a first-time film director?

No. Film school teaches theory and history, but it doesn’t teach you how to get a film made with $10,000 and a borrowed camera. Many successful directors-like Ryan Coogler, Ava DuVernay, and Quentin Tarantino-didn’t go to film school. What matters is that you’ve made something. Your film is your portfolio.

How much money do I really need to make my first feature?

You can make a compelling feature for under $10,000 if you’re smart. That covers basic gear rental, food for the crew, insurance, and festival submission fees. Most first films cost between $5,000 and $50,000. The key is not how much you spend-it’s how wisely you spend it. Avoid expensive locations, expensive actors, and expensive gear you don’t need.

Can I direct my first film without professional actors?

Yes. Many breakout films used non-professional actors. Boyhood used real kids over 12 years. Parasite cast actors based on chemistry, not résumés. Look for people who feel real in front of the camera. Test them. Record them reading lines. Watch how they react to emotion. A passionate amateur can outperform a trained actor who’s just going through the motions.

What’s the biggest mistake first-time directors make?

Trying to impress instead of connecting. Too many directors focus on fancy camera moves, dramatic lighting, or slow-motion shots to look "cinematic." But audiences remember emotion, not technique. A shaky handheld shot of someone crying is more powerful than a perfectly composed wide shot of nothing happening. Prioritize truth over style.

How do I get my film seen after the festival circuit?

Start with Vimeo On Demand or YouTube Premieres. Upload your film and sell it directly. Promote it through local screenings, Facebook groups, and Instagram reels of behind-the-scenes moments. Many indie films earn more through direct sales than through traditional distribution. Build your audience first. Distributors will come to you.

Is it too late to start directing if I’m over 30?

No. The average age of a first-time feature director in 2025 was 38. Many started after careers in teaching, nursing, or tech. Life experience gives you depth. You don’t need youth. You need urgency. The only thing that matters is that you start now.

Comments(6)