Graphic memoirs used to sit quietly on bookstore shelves, loved by a small but devoted crowd. Now, they’re opening weekend box office hits. Graphic memoirs aren’t just being adapted into films-they’re reshaping what audiences expect from true stories on screen. These aren’t flashy superhero tales. They’re raw, personal, and drawn by hand: stories about surviving trauma, navigating identity, or growing up in places the world forgot. And Hollywood is finally paying attention.

Why Now? The Rise of Illustrated Truth

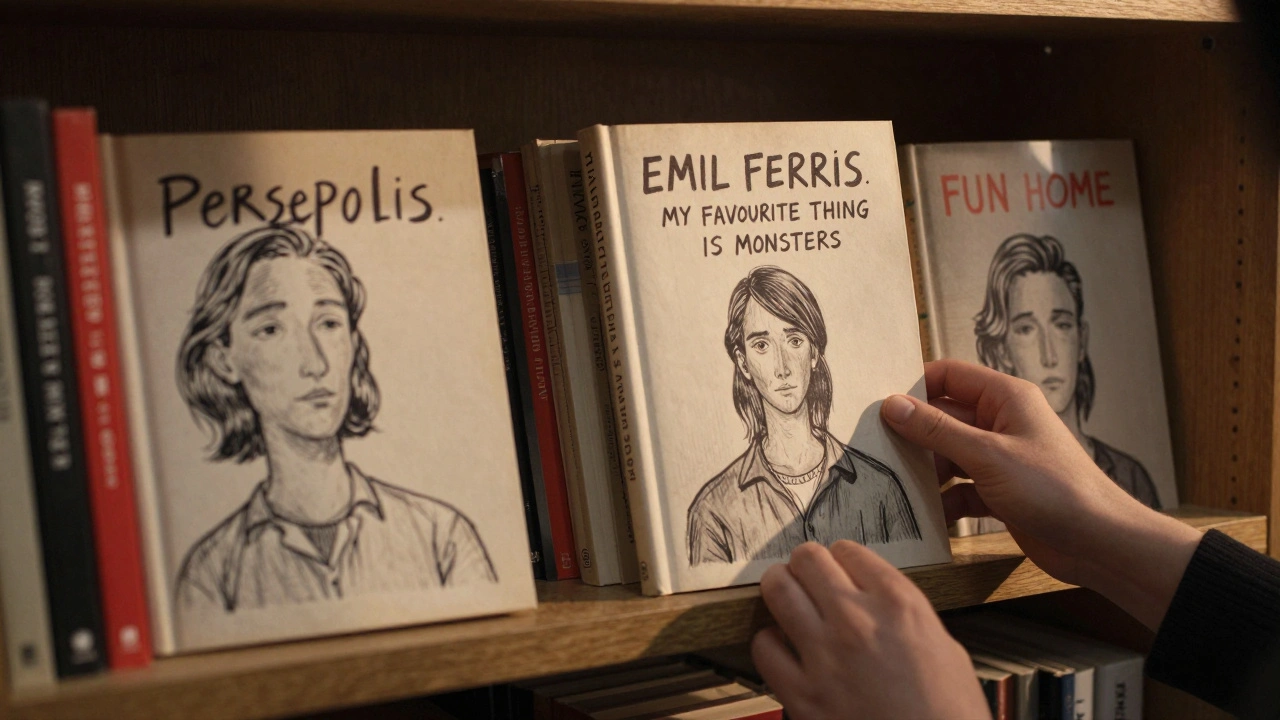

It wasn’t always this way. Ten years ago, studios thought graphic memoirs were too niche. Too quiet. Too black-and-white. But then came Persepolis in 2007, an animated adaptation of Marjane Satrapi’s story of growing up during the Iranian Revolution. It didn’t need explosions. It didn’t need A-list stars. It just needed honesty-and it earned an Oscar nomination. That proved something: people don’t need CGI to feel something deeply.

After that, the dam cracked. Fun Home, Alison Bechdel’s heartbreaking memoir about her closeted gay father and her own coming-of-age, became a Broadway musical. Then, in 2023, it was announced as a feature film in development. Hyperbole and a Half by Allie Brosh, a webcomic-turned-book about depression and absurdity, was picked up by Universal. My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, Emil Ferris’s 700-page illustrated tale of a girl investigating her neighbor’s murder while grappling with her own identity as a Mexican-American queer child, is now in pre-production with A24.

Why the sudden shift? Audiences are tired of polished, sanitized biopics. They want texture. They want the messy, handwritten, emotionally unfiltered truth-and graphic memoirs deliver that in a way traditional prose can’t. The drawings aren’t just decoration. They’re the emotion made visible.

The Visual Language of Memory

What makes graphic memoirs so powerful in adaptation isn’t just the story-it’s how it’s drawn. Lines wobble when someone is scared. Colors bleed when grief hits. Panels shrink when time slows down. These aren’t just artistic choices. They’re psychological tools.

In March, John Lewis’s three-volume memoir of the Civil Rights Movement, the art uses heavy shadows and stark contrasts to show the weight of violence. When adapted into a film, those visual metaphors had to be translated-not copied. The filmmakers didn’t animate the drawings. They used lighting, framing, and color grading to echo the same emotional tone. That’s the secret: it’s not about turning panels into moving images. It’s about turning feeling into film.

Take Ghost World, adapted from Daniel Clowes’s 2001 graphic novel. The movie didn’t try to replicate the flat, comic-book aesthetic. Instead, it used real locations-dusty diners, empty parking lots, suburban streets-and shot them with the same detached, ironic gaze that Clowes used in his panels. The result? A film that felt like the book even though it looked nothing like it.

Who’s Behind the Scenes?

These adaptations aren’t being led by studio executives who’ve never opened a graphic novel. They’re being driven by filmmakers who grew up reading them.

Director Alma Har’el, who adapted Boyhood author Richard Linklater’s unpublished graphic memoir into the 2024 film It’s All True, said in an interview: “I didn’t just read the book. I lived inside it. I drew in my journals the same way the protagonist did. That’s how I knew how to shoot it.”

Many of the directors and writers now working on these projects are former comics fans. Some even started as cartoonists themselves. The team behind My Favorite Thing Is Monsters includes a former indie comic artist who spent five years sketching storyboards that matched the original book’s page layout. The producer, a former librarian, insisted on keeping every handwritten caption exactly as written-no rewrites.

This isn’t Hollywood trying to cash in. It’s artists honoring artists.

The Challenges of Translation

Not every graphic memoir survives the jump to film. Some fail because they try too hard to be faithful. Others fail because they abandon the soul of the original.

Take Blankets by Craig Thompson. The 2003 graphic novel is over 500 pages of intricate, flowing linework. It’s about first love, religious guilt, and sibling bonds. When a film adaptation was announced in 2018, fans worried: How do you animate a 500-page wordless passage where the only sound is snow falling? The studio eventually shelved the project. Why? Because they realized: you can’t. Not without losing what made it special.

On the flip side, Black Hole by Charles Burns was adapted into a limited series in 2025. Instead of trying to animate the grotesque, surreal body horror, the show used practical effects and prosthetics-exactly how Burns drew it. The result? Critics called it “the most faithful adaptation of a graphic novel ever made.”

The lesson? Don’t copy the style. Copy the intent.

What’s Next? The New Wave of Memoirs in Line

The pipeline is full. Here are five graphic memoirs currently in active development as feature films:

- Fun Home by Alison Bechdel - Directed by Sam Mendes, set for 2026 release

- My Favorite Thing Is Monsters by Emil Ferris - A24, in pre-production, casting begins early 2026

- Are You My Mother? by Alison Bechdel - A companion piece to Fun Home, in early scripting with Netflix

- El Deafo by Cece Bell - Animated film by DreamWorks, targeting 2027 release

- Stitches by David Small - Directed by Guillermo del Toro, based on his childhood illness and silence

These aren’t just stories about trauma. They’re stories about voice. About finding your way back to yourself after being told to stay quiet. That’s why they’re resonating now. In a world full of curated feeds and polished personas, these books scream: I was real. And I’m still here.

Why This Matters Beyond the Screen

This trend isn’t just about movies. It’s about who gets to tell their story-and how.

For decades, memoirs by women, LGBTQ+ people, immigrants, and people with disabilities were dismissed as “too niche” or “too strange.” Graphic memoirs changed that. They gave marginalized voices a language that bypassed traditional publishing gatekeepers. You didn’t need a literary agent. You just needed a pen, paper, and the courage to draw your truth.

Now, those stories are hitting theaters. That means more kids growing up seeing themselves on screen-not as side characters, not as stereotypes, but as complex, flawed, beautiful humans drawn with care.

And that’s the real win. Not box office numbers. Not awards. It’s a kid in rural Ohio picking up Stitches and thinking: “That’s me. Someone else felt this too.”

Why are graphic memoirs being adapted into films now?

Graphic memoirs are being adapted now because audiences are craving authentic, emotionally raw stories that feel real-not polished or scripted. These books use visual storytelling to convey inner emotions in ways traditional prose can’t, and filmmakers who grew up reading them are now in positions to bring those stories to life with respect and depth.

Do graphic memoirs need to look like comics in the movies?

No. The best adaptations don’t copy the art style-they capture the emotional tone. A film might use lighting, color, and camera movement to echo the mood of the drawings, not replicate them frame-for-frame. Ghost World and March both succeeded by translating feeling, not pixels.

What’s the difference between a graphic novel and a graphic memoir?

A graphic novel can be fiction, fantasy, or speculative. A graphic memoir is always autobiographical. It’s a true story told through drawings-about the author’s own life, memories, and emotions. Think Persepolis (memoir) vs. Watchmen (fiction).

Are graphic memoir adaptations more successful than other comic adaptations?

They often are-critically, at least. While superhero films dominate box office numbers, graphic memoir adaptations like Persepolis and March consistently earn higher ratings on Rotten Tomatoes and win awards for storytelling and direction. They connect because they’re honest, not because they’re loud.

Can any graphic memoir become a movie?

Not every one should. Some stories are too intimate, too visual, or too quiet to work in film without losing their power. The key is matching the story’s soul to the right medium. If a memoir lives in silence and stillness, forcing it into action sequences can ruin it. The best adaptations know when to stay still.

Comments(6)