Why Ethics in Documentary Filmmaking Isn’t Optional

People trust documentaries. They believe what they see on screen is real - raw, unfiltered, true. But behind every powerful moment, there’s a human being who gave something up: their story, their privacy, their dignity. And too often, that person never fully understood what they were giving.

Documentary filmmakers don’t just capture reality. They shape it. The camera doesn’t just record - it changes everything. A subject might think they’re telling their story to raise awareness. But what if the final edit turns them into a stereotype? What if they’re never paid? What if they’re left with no control over how their life is used after the film ends?

This isn’t about being perfect. It’s about being responsible.

Consent Isn’t Just a Signature on a Form

Most filmmakers get signed release forms. They check the box. They think they’re covered. But consent isn’t a legal document. It’s a conversation - and it should keep happening.

Take the case of a rural family in Appalachia filmed for a documentary about poverty. They signed the form. They thought the film would show how hard they worked to keep their home. Instead, the final cut focused only on their broken furniture and lack of running water. They didn’t recognize themselves. They felt exploited.

True consent means the subject understands how their image will be used, who will see it, and how it might affect them. It means explaining editing choices. It means saying, “This part might make you look angry. Is that okay?”

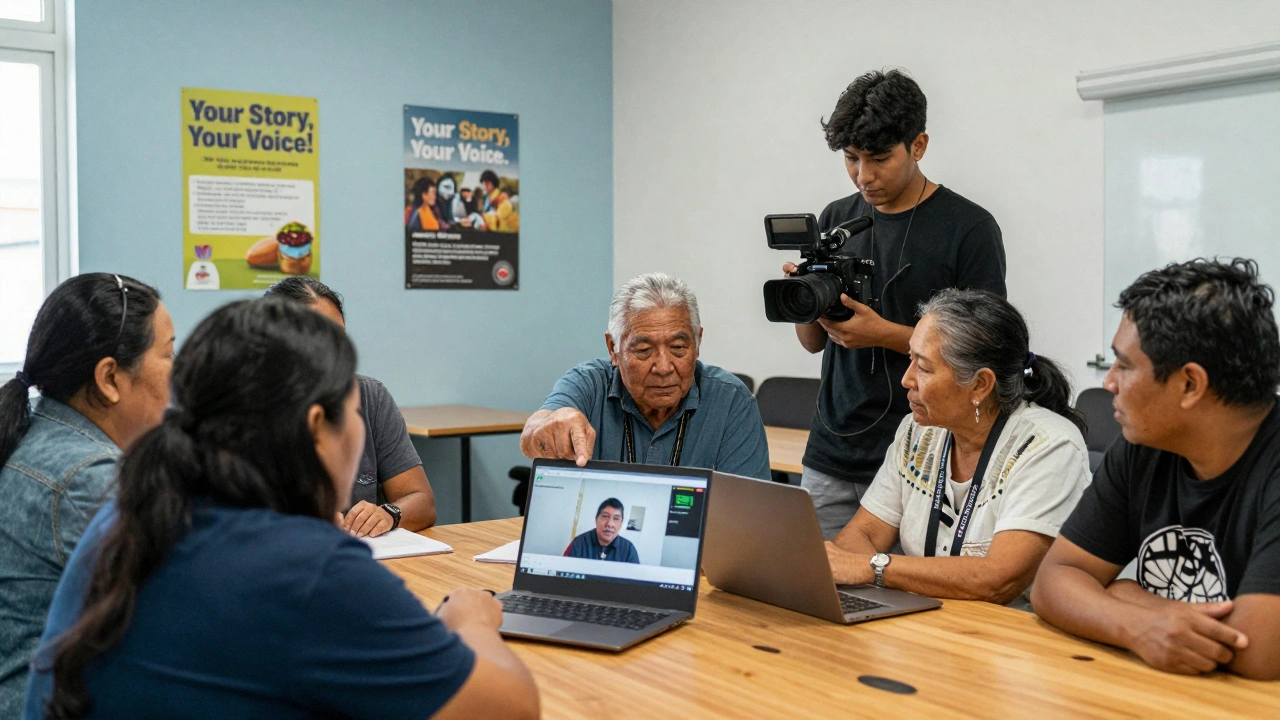

Some filmmakers now use ongoing consent. They check in months after filming. They send rough cuts. They let subjects pull their footage. One documentary team working with Indigenous communities in Canada gave participants the right to veto any scene - even after the film was finished. That’s not just ethical. It’s respectful.

Access Isn’t a Right - It’s a Privilege You Earn

Access is the lifeblood of documentary filmmaking. But who gets to say who gets in?

Some filmmakers show up with a camera and assume they deserve entry. They think their story matters more than the subject’s comfort. They push past boundaries. They film in hospitals, homes, and courtrooms without permission. They call it “journalism.” It’s not. It’s invasion.

Real access is built slowly. It’s showing up week after week without a camera. It’s sharing your own story first. It’s listening more than you speak. It’s offering help - fixing a leaky roof, helping with childcare - before asking for footage.

One filmmaker spent six months living in a homeless shelter before turning on her camera. She didn’t ask for interviews until people started asking her about the film. That’s how trust is built. That’s how you get access that’s real, not performative.

And sometimes, you don’t get access at all. And that’s okay. Some stories aren’t yours to tell. You don’t need to film everything to make a good documentary. Sometimes the most powerful choice is to walk away.

Power Isn’t Just Who Holds the Camera - It’s Who Controls the Narrative

The person holding the camera holds the power. But the real power lies in who decides what the story means.

Think about the classic documentary trope: the poor person speaking to the camera with a sad expression, while the narrator says something like, “This is what happens when systems fail.” The subject becomes a symbol. Not a person.

That’s not storytelling. That’s exploitation.

Power in documentary filmmaking isn’t just about access. It’s about authorship. Who gets to name the problem? Who defines the solution? Who gets the credit?

Some filmmakers now practice collaborative storytelling. They give subjects co-writing credits. They let them choose the music. They let them narrate their own story in their own words. One film about refugees in Greece had its subjects edit their own interviews. The result? A raw, honest, deeply human film that no outsider could have made.

When the subject becomes a co-creator, the power shifts. And the story becomes stronger.

What Happens After the Credits Roll?

Most documentaries end with a final shot and a fade to black. But for the people in the film, the story doesn’t stop.

Some subjects face harassment after their film airs. Others lose jobs. Some are stalked online. One woman featured in a film about domestic violence was recognized in her town - and her abuser found her. The filmmaker had no plan to protect her.

That’s not just negligence. It’s cruelty.

Ethical filmmakers don’t just think about the film. They think about the aftermath. They build support networks. They connect subjects with counselors. They set up privacy protections. They negotiate with distributors to limit where and how the film is shown.

Some even create aftercare funds - small grants for subjects to cover therapy, legal help, or relocation. One documentary about formerly incarcerated people set aside 10% of its profits to help participants rebuild their lives. That’s not charity. That’s accountability.

The Myth of the “Neutral” Filmmaker

Many filmmakers claim they’re just observers. “I’m not making a judgment,” they say. “I’m just showing the truth.”

But there’s no such thing as neutral filmmaking.

Choosing what to film. Choosing what to cut. Choosing where to place the camera. Choosing who to interview. All of these are decisions - and each one carries bias.

Even the way you frame a shot can imply guilt, innocence, strength, or weakness. A low angle makes someone look powerful. A close-up on trembling hands makes them look broken.

Instead of pretending to be neutral, ethical filmmakers own their perspective. They say, “This is my view. This is what I saw. This is what I believe.” They let the audience know where they stand.

And they invite criticism. They welcome feedback from the subjects. They release behind-the-scenes footage. They admit when they got something wrong.

Honesty about bias doesn’t weaken a documentary. It makes it stronger.

What Should You Do If You’re Making a Documentary?

- Don’t rely on a one-time release form. Keep talking. Let subjects review cuts. Give them the power to withdraw.

- Build trust before you film. Spend time with people. Don’t bring the camera until they ask for it.

- Give credit where it’s due. If someone helped shape the story, list them as a co-creator.

- Plan for consequences. What happens to the subject after the film? Have a safety plan.

- Don’t pretend you’re neutral. Say where you stand. Be clear about your role.

- Pay your subjects. If your film makes money, share it. If you can’t pay, offer something real - healthcare, legal aid, education.

What If You’re the Subject?

If you’re being filmed, you have rights too.

- Ask: “How will this be used?” “Who will see it?” “Can I change my mind later?”

- Don’t sign anything you don’t understand. Ask for a copy in plain language.

- Request a rough cut. You have the right to see how you’re portrayed before it’s finished.

- If something feels wrong, say so. Walk away. Your story is yours.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Documentary filmmaking is changing. More filmmakers are listening. More subjects are demanding control. More festivals are requiring ethical guidelines.

The International Documentary Association now has a Statement of Best Practices that includes consent, compensation, and post-production support. Many universities now teach ethics as part of every documentary course.

But progress isn’t automatic. It takes effort. It takes courage. It takes humility.

The best documentaries aren’t the ones that win awards. They’re the ones that leave the people in them better off than they were before the camera turned on.

Is it ethical to film someone without their permission if it’s for a public interest story?

No. Even stories about public figures or social issues require informed consent. Public interest doesn’t override personal rights. Filming someone without consent - even if they’re in public - can cause lasting harm. Ethical filmmakers find ways to tell important stories without violating dignity. There are always alternatives: using voiceovers, anonymizing faces, or waiting until permission is given.

What if a subject changes their mind after signing a release?

Ethical filmmakers honor that change. A signed release is not a contract that overrides humanity. If someone asks to remove their footage, you have a moral obligation to comply - even if it means reshooting or cutting key scenes. Some filmmakers include a “right to withdraw” clause in their agreements. It’s not legally binding everywhere, but it’s the right thing to do.

Do documentary filmmakers have to pay their subjects?

Legally, no - unless it’s part of a contract. Ethically, yes, if the film makes money. Subjects give time, trust, and emotional labor. If you profit from their story, sharing that profit isn’t optional - it’s fair. Many filmmakers now use profit-sharing models or set aside funds for subjects. If you can’t pay cash, offer services: therapy, legal help, education, or housing support.

Can I film in a hospital or school without permission?

No. Even if you’re filming in a public space, institutions like hospitals and schools have privacy policies and legal protections. Filming without permission violates both ethics and often the law. Always get written consent from the institution and from every individual being filmed. There’s no exception for “important stories.”

What if my subject is a child or someone with limited mental capacity?

You need consent from a legal guardian - but that’s not enough. You must also ensure the child or person understands, to the best of their ability, what’s happening. Use simple language. Show them what the camera does. Let them ask questions. If they seem uncomfortable, stop. Never pressure. Never exploit vulnerability. Their safety comes before your story.

Comments(5)