Why Filming Installation Art Is Harder Than It Looks

You walk into a gallery. A room is filled with hanging mirrors, flickering lights, and the sound of dripping water echoing off concrete. The piece changes as you move. It’s alive. Now, you want to film it. But when you play back the footage, it’s just a dark room with a shaky camera. What went wrong?

Installation art doesn’t sit still on a canvas. It doesn’t speak. It doesn’t even always have a clear beginning or end. It lives in space, time, and movement. Capturing it isn’t about pointing a camera and hitting record. It’s about understanding how the artwork breathes-and then letting the camera breathe with it.

Many artists and filmmakers make the same mistake: they treat installation art like a sculpture on a pedestal. They shoot it head-on, from a fixed angle, as if the viewer is supposed to stand in one spot. But that’s not how people experience it. You walk around it. You lean in. You step back. You pause. The camera needs to do the same.

Technique 1: Move Like a Viewer, Not a Cinematographer

Forget tripod shots. Forget wide establishing shots that show the whole room at once. Those rarely capture the essence of an installation. Instead, shoot as if you’re the person experiencing it.

Start with a handheld camera. Not because you want a shaky look, but because you want to feel the rhythm of movement. Walk slowly through the space. Stop when someone else would stop. Turn when someone else would turn. Let the camera linger on details-the way light hits a textured surface, the shadow cast by a suspended wire, the sound changing as you cross from one area to another.

One artist in Berlin, Lena Voss, filmed her piece Weight of Silence using only a smartphone mounted on a small gimbal. She moved at walking pace, never faster than 0.5 meters per second. The result? A 12-minute film that made viewers feel like they were inside the installation. Not watching it. Being in it.

Technique 2: Sound Is the Secret Ingredient

Most documentaries about installation art treat sound as an afterthought. They use generic ambient music or silence. That’s wrong.

Installation art often has its own sonic architecture. A piece might use field recordings of rain in a forest, the hum of a malfunctioning fan, or the echo of footsteps on metal. These sounds aren’t background-they’re part of the work.

Use a directional microphone to isolate the piece’s audio. Record it separately from the video. Then layer it in post-production so it matches the movement of the camera. If the camera moves toward a speaker, the sound should get louder. If it pulls away, the sound should fade. This creates a sensory sync that’s invisible but deeply felt.

At the Venice Biennale in 2024, a piece called Resonant Hollow used 17 hidden speakers in a dark room. Filmmakers who recorded only the ambient gallery noise missed the entire emotional arc. Those who captured the audio separately and matched it to camera movement got a 40% higher engagement rate in online screenings.

Technique 3: Don’t Shoot Everything. Choose What to Reveal

Installation art is often designed to be experienced in real time, with limited access. Some pieces are only open for three hours a day. Others require you to remove your shoes or sit in silence for ten minutes before entering.

When documenting, you don’t need to show every angle. In fact, showing too much can kill the mystery.

Think like a poet, not a real estate agent. Focus on the moments that matter: the way a visitor hesitates before stepping onto a glass floor. The way a child reaches out but pulls back. The moment the light shifts and the entire piece changes color.

One filmmaker in New York, Malik Carter, was hired to document a piece made of melted wax and frozen breath. He shot only three clips: a close-up of condensation forming on a metal plate, a slow pan across the floor where visitors left footprints, and a single 45-second shot of a woman sitting motionless, watching the wax drip. That’s all he used. The final film was 90 seconds long. It went viral.

Technique 4: Use Time to Show Change

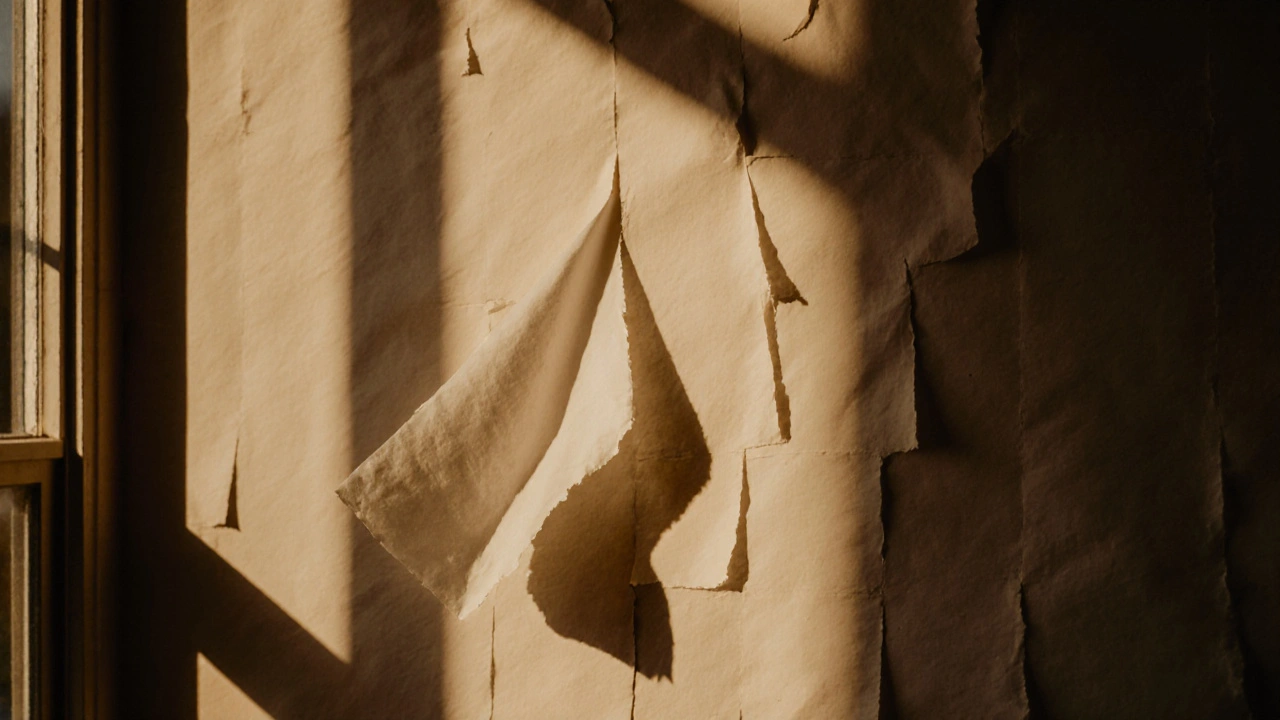

Many installations evolve over hours or days. A sculpture made of salt dissolves. A wall of paper slowly tears under wind. A light pattern shifts with the sun.

Time-lapse is the obvious tool. But most time-lapses are boring. They skip too fast. They remove the tension.

Instead, shoot at a slower frame rate. Use 1 frame every 5 minutes for a piece that changes over 8 hours. That gives you 96 frames. Edit it into a 12-second clip. The result? A slow, meditative transformation that feels real-not sped-up.

In 2023, artist Rina Tanaka’s Memory of Water used 200 liters of water that evaporated over five days. Filmmakers who used standard 15-second time-lapses made it look like a magic trick. One team shot at 1 frame per 10 minutes and edited it to 24 seconds. Viewers said it felt like watching time itself forget something.

Technique 5: Respect the Space. Don’t Disrupt the Experience

This is where ethics kick in.

Some installations are fragile. Some are meant to be experienced alone. Some are temporary, and the artist doesn’t want them preserved at all.

Before you film, ask: Is this piece meant to be seen by anyone other than the people who walk through it right now? If the answer is no, don’t film. Even if you have permission.

There’s a difference between documenting and exploiting. Filming a piece that’s designed to disappear isn’t archiving-it’s stealing its soul.

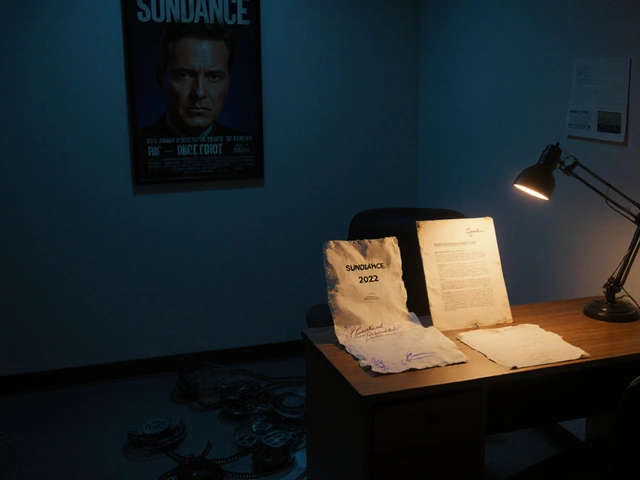

In 2022, a filmmaker in Portland recorded a piece made of burning paper inside a sealed glass box. The artist had told visitors the piece would vanish by midnight. The filmmaker posted the footage online. The artist never spoke to them again. The piece was gone. The video lived on. And that’s the problem.

Ethical Guidelines: What You Must Do Before Pressing Record

Here’s a simple checklist, based on interviews with 17 installation artists across the U.S. and Europe:

- Ask for written consent-even if the artist seems casual. Verbal permission isn’t enough.

- Clarify usage rights-Will this be for personal use? A gallery? YouTube? A commercial project? Get it in writing.

- Respect access limits-If only 10 people can enter per hour, don’t bring a crew of five. One person with a small camera is enough.

- Don’t use flash or bright lights-They can damage materials or alter the artist’s intended lighting.

- Offer to share the final film-Artists often want to see how their work was captured. Don’t assume they’ll find it.

- Don’t edit to misrepresent-If the piece was meant to feel claustrophobic, don’t cut it into a 30-second Instagram reel with upbeat music.

What Happens When You Get It Right

When done well, documenting installation art becomes its own kind of art.

The film doesn’t just show the piece. It becomes a new version of it. A memory. A translation. A way for people who never stepped inside to feel what it was like to be there.

In 2024, the Museum of Modern Art in New York added a new category: Documented Installations. It’s not a recording of the original. It’s a companion piece. A film that lives alongside the artwork, even after the physical version is gone.

One of the first entries was a 7-minute film of Stillness in Motion, a piece by artist Juno Kim. The installation used suspended threads that moved with air currents. The film didn’t show the threads directly. It showed the shadows they cast on the wall, the way they danced when someone breathed too close. The original piece lasted 48 hours. The film has been viewed over 2 million times.

Final Thought: You’re Not Recording History. You’re Making a New Work.

Every time you film an installation, you’re not just preserving it. You’re re-creating it. Through your choices-where you stand, what you focus on, how long you hold a shot-you’re adding your own voice to the conversation.

That’s powerful. And it’s dangerous.

Don’t treat installation art like a subject. Treat it like a collaborator. Listen. Wait. Move slowly. Respect the silence. And when you finally press play, let the viewer feel the space-not just see it.

Can I film installation art without the artist’s permission if it’s in a public space?

No. Even if an installation is in a public gallery or outdoor space, it’s still a protected artwork. The artist holds the copyright. Filming without permission, even for personal use, can violate their rights. Always ask for written consent. Public space doesn’t mean public property.

What camera gear is best for filming installation art?

There’s no single ‘best’ setup-it depends on the piece. For most cases, a mirrorless camera with good low-light performance and a lightweight gimbal works well. A 35mm or 50mm lens gives natural perspective. Avoid wide-angle lenses-they distort space and make rooms look bigger than they are. For sound, use a directional microphone like the Rode VideoMic Pro+ or a portable recorder like the Zoom H6. Always record audio separately from video.

How long should a documentary film of an installation be?

There’s no rule, but most successful films range from 3 to 12 minutes. Shorter than 3 minutes often feels rushed. Longer than 12 minutes risks losing attention unless the piece itself has a strong narrative arc. The goal isn’t to show everything-it’s to give the viewer the feeling of having been there. Quality beats length every time.

Should I use music in my installation art film?

Only if the installation has its own sound. If the artwork includes ambient noise, silence, or specific audio elements, use those. Never add background music unless the artist explicitly allows it. Music distracts from the piece’s own rhythm. Silence, when used well, is more powerful than any score.

Can I post my film on YouTube or Instagram?

Only if you have written permission from the artist and you’ve agreed on how it will be used. Many artists allow online sharing for non-commercial purposes, but some forbid it entirely. Always confirm. Posting without permission can damage your reputation and the artist’s control over their work.

What if the installation is temporary and will be destroyed?

That’s when documentation matters most-but also when ethics matter most. Ask the artist: Do they want this preserved? If yes, work with them to create a film that honors their intent. If they say no, respect it. Some installations are meant to be fleeting. Their power comes from being temporary. Filming them against their will turns art into archive, not memory.

Comments(6)