China and India are two of the biggest film markets in the world. Together, they have over 2.5 billion people, thousands of theaters, and growing audiences hungry for stories that feel real. But despite their size and shared interest in global storytelling, very few films are made together. Why? Because making a co-production between China and India isn’t just about funding or talent-it’s about navigating a minefield of government rules, censorship, and market barriers that few outsiders understand.

Co-production treaties exist, but they’re not easy to use

China has signed co-production treaties with more than 20 countries, including India. The India-China co-production agreement was signed in 2017 and renewed in 2023. On paper, it sounds simple: both countries contribute funding, talent, and creative input. The final film gets treated as a domestic production in both markets, meaning it avoids foreign film quotas and gets better theater access.

In reality, the treaty is more like a checklist than a roadmap. To qualify, a co-production must meet strict criteria. For China, at least 30% of the budget must come from Indian sources, and at least 30% of the principal cast and crew must be Indian. India requires similar shares. But here’s the catch: China’s State Administration of Radio and Television (SART) has final say on whether a film qualifies-and they don’t always share their reasoning.

Only three co-productions have officially cleared the Chinese approval process since 2017. One of them, The Himalayan Warrior (2021), was a historical drama shot in Ladakh and Yunnan. It barely broke even. Another, a fantasy film called Dragon’s Breath (2023), was pulled from Chinese theaters two weeks after release because a character’s costume was deemed “culturally insensitive.” No official explanation was given.

Censorship isn’t just about politics-it’s about cultural fit

China’s censorship system doesn’t just block political content. It blocks anything that doesn’t fit its vision of “harmony.” That includes religious symbolism, romantic relationships that cross ethnic lines, and even certain colors or music styles that are seen as too “Western” or “foreign.”

Indian filmmakers quickly learn this when they pitch stories. A script about a Muslim girl in Kashmir falling in love with a Chinese soldier? Dead on arrival. A comedy about a Bollywood star getting lost in Shanghai? Possible-if the Chinese side insists the character learns to respect Chinese traditions by the end. A documentary on air pollution in Beijing? Only if it ends with a government-led cleanup initiative.

Indian producers say they’ve rewritten entire scripts to remove references to Tibet, Taiwan, or historical conflicts. Some have even changed character names to sound more “Chinese-sounding,” even if it makes no sense in the story. One producer told me they cut 17 minutes of dialogue because a character mentioned “freedom of speech” in a scene set in Mumbai. The Chinese co-producer said it “could confuse audiences.”

Meanwhile, India’s Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) has its own rules. Films with too much Chinese dialogue, or that show Chinese characters as dominant or superior, get flagged. A 2022 film, Shanghai Nights, was denied a release certificate because a Chinese businessman was portrayed as more successful than the Indian lead. The board called it “unpatriotic.”

Market access is the real prize-and it’s tightly controlled

China limits foreign films to just 34 releases per year. India doesn’t have a hard cap, but it’s harder to get screens in major cities if you’re not a Bollywood film or a Hollywood blockbuster. Co-productions are supposed to bypass these limits, but in practice, they’re treated like foreign films unless they pass the government’s cultural test.

Chinese distributors don’t want to risk a film that might get pulled mid-run. So they avoid co-productions unless they’re sure they’ll get approval. Indian distributors don’t want to invest in a film that might be banned in China. So they avoid it too.

The result? A chicken-and-egg problem. No one wants to fund a co-production because the market access isn’t guaranteed. But without funding, the film can’t get approved. The only co-productions that succeed are those backed by state-owned studios on both sides. For example, One Sky, One Dream (2024), a sports drama co-produced by China Film Group and Reliance Entertainment, got wide release in both countries because it was funded by government-backed entities and focused on Olympic training.

What works-and what doesn’t

There are patterns in what gets approved. Films that focus on:

- Shared heritage (ancient trade routes, Buddhist history)

- Environmental themes (Himalayan conservation, river pollution)

- Family dramas with universal values (love, sacrifice, duty)

- Historical figures who are respected in both cultures (like Marco Polo or Xuanzang)

These films get greenlit because they’re seen as “safe.” They don’t challenge national identity or bring up sensitive topics.

What fails?

- Contemporary political stories

- Stories with LGBTQ+ characters

- Any mention of border disputes

- Comedy that mocks authority

- Horror or fantasy with supernatural elements tied to non-state religions

One indie producer tried to make a ghost story set in the 1962 Sino-Indian War. The script was rejected by both countries. The Chinese side said it “distorted history.” The Indian side said it “glorified conflict.”

Who’s trying to break the mold?

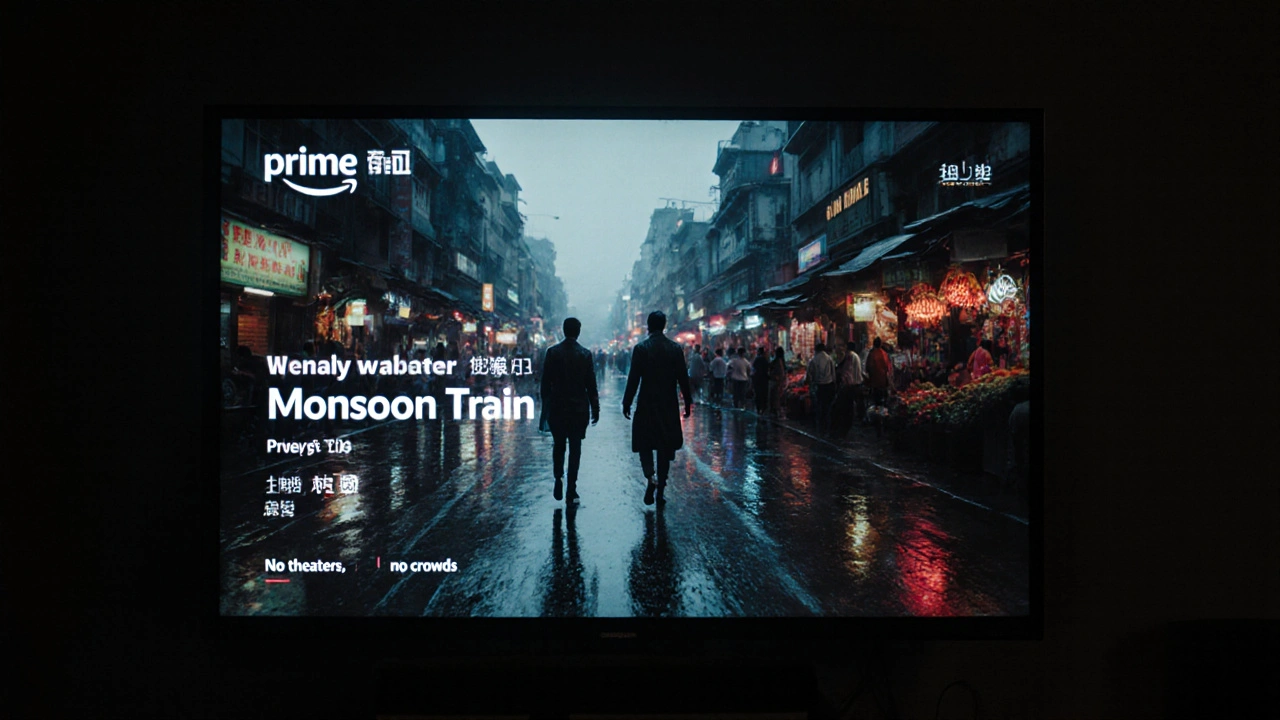

A few independent producers and streaming platforms are finding ways around the system. Netflix and Amazon Prime have started funding co-productions that are released as originals on their platforms-bypassing theatrical quotas entirely. In 2024, Monsoon Train, a crime thriller shot in Mumbai and Kunming, premiered on Prime Video in both countries without ever entering theaters.

That’s the new path: digital-first. No need for government approval. No need to fight for screen time. Just make the film, upload it, and let audiences decide. The downside? No box office revenue. No prestige. And no guarantee the film won’t be taken down later if it violates local laws.

Some filmmakers are also using “third-country” production companies to act as buffers. A film might be legally registered as a Singapore-India co-production, with Chinese talent hired as freelancers. It’s a gray area, but it’s working for a few low-budget projects.

The future isn’t in theaters-it’s in collaboration

China and India won’t suddenly become easy partners for film. The political tensions, cultural differences, and censorship systems won’t vanish. But the demand for content is growing. Young audiences in both countries are watching more global films than ever. They’re tired of the same Hollywood formulas. They want stories that reflect their own realities.

The real opportunity isn’t in big-budget blockbusters. It’s in small, authentic stories-told with local voices, filmed on location, and distributed digitally. A documentary about a Tibetan monk teaching yoga in Bangalore. A web series about a Chinese chef opening a curry restaurant in Chengdu. A short film about two teenagers, one in Delhi and one in Shanghai, texting about their dreams.

These don’t need government approval. They don’t need to clear quotas. They just need to be honest. And right now, that’s the rarest kind of co-production of all.

Can China and India make a successful co-production film today?

Yes, but only under strict conditions. Successful co-productions are usually low-budget, digitally released, and avoid political or cultural sensitivities. Government-backed projects like One Sky, One Dream have succeeded in theaters, but independent films rarely survive the approval process. Digital platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime are becoming the most viable route.

Why are there so few China-India co-productions compared to China-US or India-UK ones?

China has deeper cultural and political barriers with India than with Western countries. The border dispute, historical mistrust, and differing censorship priorities make collaboration harder. Western countries often have more flexible cultural frameworks and established distribution channels. India and China also have less industry overlap-Bollywood and Chinese cinema operate in very different styles and markets.

Do Indian actors get cast in Chinese films?

Rarely. When they do, it’s usually in minor roles-tourists, servants, or background characters. Leading roles for Indian actors in Chinese films are almost nonexistent unless the project is a co-production. Even then, Chinese studios often cast Chinese actors in Indian roles to avoid cultural friction. The reverse is also true: Chinese actors rarely appear in mainstream Indian films.

Can streaming platforms bypass censorship in China and India?

Not completely. Both countries have strict digital censorship laws. Netflix and Amazon must comply with local regulations to operate. They self-censor content to avoid being blocked. A film might be available in India but removed in China, or vice versa. However, streaming avoids the worst of theatrical quotas and delays, making it the least restrictive path for co-productions today.

What’s the biggest mistake filmmakers make when trying to co-produce between China and India?

Assuming the two markets are similar. They’re not. China’s system is top-down and centralized. India’s is decentralized and politically fragmented. What’s acceptable in one country can be banned in the other. Filmmakers who don’t hire local legal and cultural consultants early on end up wasting years on scripts that will never be approved.

Comments(7)