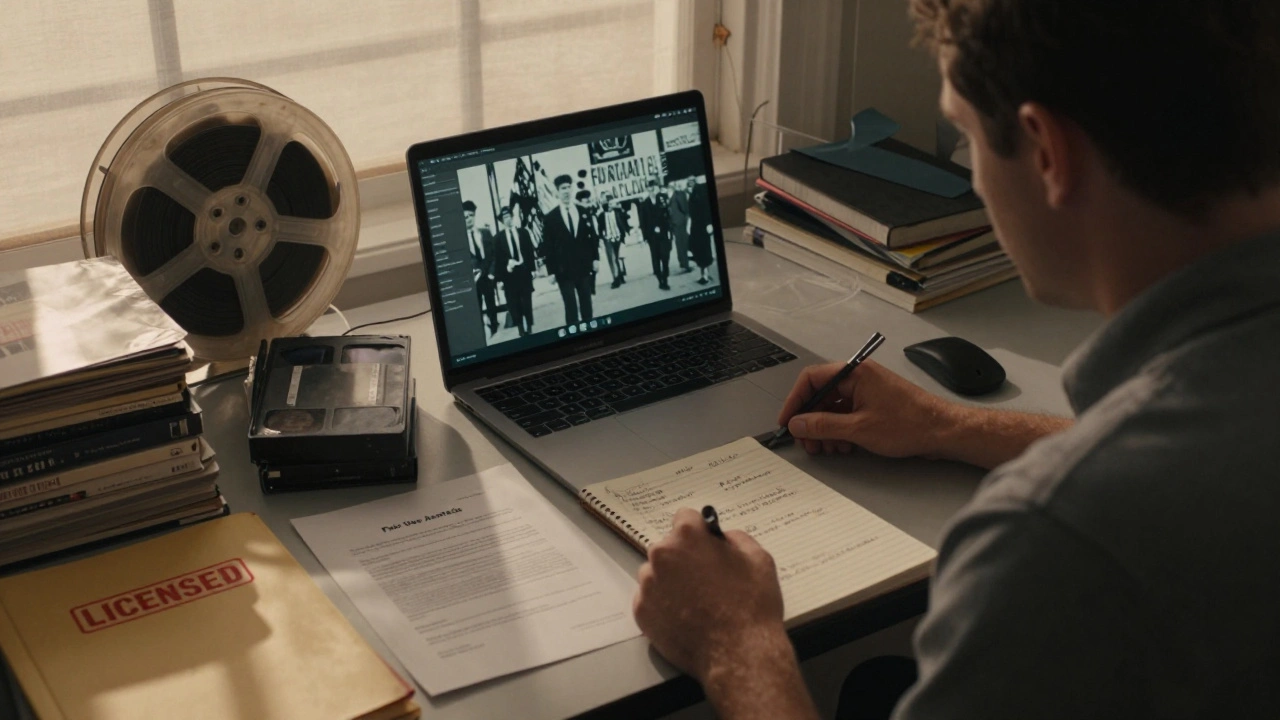

You’re editing your documentary. You found the perfect clip-a 1968 protest march, grainy but powerful. It’s exactly what your story needs. But when you try to use it, someone says, "You can’t just take that. It’s copyrighted." Now what?

Archival footage is the backbone of most serious documentaries. It’s how we see history come alive: civil rights marches, moon landings, war footage, forgotten TV ads, home movies from the 1950s. But using it isn’t as simple as downloading and dropping it in. If you don’t know the rules, you could be sued-or worse, have your film pulled from festivals and streaming platforms.

What Counts as Archival Footage?

Archival footage isn’t just old videos. It’s any pre-existing motion picture or video material you didn’t shoot yourself. That includes:

- Newsreels from the 1940s

- Home movies uploaded to YouTube by a stranger

- Corporate training films from the 1970s

- Television broadcasts, even if they aired decades ago

- Film clips from Hollywood movies

Just because something is old doesn’t mean it’s free to use. Copyright lasts for decades-even up to 95 years after publication in the U.S. A 1955 news clip? Still protected. A 1920 silent film? Maybe public domain. But you can’t assume. You have to check.

Fair Use: The Legal Loophole Everyone Talks About

Most filmmakers hope they can rely on fair use. It’s the legal doctrine that lets you use copyrighted material without permission under certain conditions. But it’s not a free pass. Courts don’t decide fair use based on your intentions-they look at four specific factors.

- Purpose and character of the use - Are you using it for education, commentary, or criticism? Or just to fill screen time? Transformative use matters. If you’re analyzing the clip to show how media shaped public opinion during the Vietnam War, that’s strong fair use. If you’re just playing the clip as background footage while someone talks over it? Weak.

- Nature of the copyrighted work - Factual content (news footage, government films) gets more protection than creative works (movies, music videos). But even factual clips can be protected if they were originally produced for commercial distribution.

- Amount and substantiality used - How much of the original did you take? Using a 30-second clip from a two-hour news broadcast is better than using the entire two hours. Even a five-second clip can be too much if it’s the most important or recognizable part-the "heart" of the work.

- Effect on the market - Will your use replace the original? If someone could watch your documentary instead of buying the original footage, you’re in trouble. If your documentary is about the 1969 moon landing and you use a 12-second NASA clip, that’s fine. But if your whole film is just a compilation of NASA footage with no commentary? That’s a problem.

There’s no magic formula. A judge looks at all four together. Courts have ruled in favor of documentaries like Exit Through the Gift Shop and The Fog of War because they transformed the footage into new meaning. But they’ve also ruled against films that used clips too casually.

When Fair Use Doesn’t Work

Some situations are clear-cut: you can’t claim fair use if:

- You’re using footage for entertainment value only-no analysis, no critique, no context.

- You’re using it as a visual prop to make your film look "professional" without adding value.

- You’re copying the exact same version used in a commercial archive (like a well-known news network’s original broadcast).

- You’re making money from it and the original rights holder could reasonably expect to license it.

Here’s a real example: A filmmaker used a 10-second clip of a 1980s commercial for a toy robot. The clip was funny, nostalgic, and fit the tone. But the toy company still owned the rights. Even though the clip was short, the court ruled it was used to attract viewers-and that hurt the company’s ability to license it to others. The filmmaker had to pay $15,000 in damages.

Licensing Archival Footage: The Safe Way

If fair use is risky, licensing is the fallback. It’s expensive, but it’s clean. You pay for the right to use the footage, and you get legal protection.

Major archives include:

- AP Archive - News footage from 1895 to today. Prices start at $500 for a 30-second clip.

- Getty Images - Stock footage, historical photos, and video. Licensing fees vary by usage (broadcast, streaming, educational).

- Internet Archive - Free public domain material. You can download and use thousands of clips, but verify the copyright status yourself.

- Library of Congress - Many government-produced films are public domain. Check their catalog for titles marked "No known copyright restrictions."

Licensing isn’t just about money. You also need to get the right type of license:

- Non-exclusive - Others can use the same clip. Fine for documentaries.

- Exclusive - You’re the only one who can use it. Overkill unless you’re making a competing film.

- Worldwide vs. regional - If you’re only screening in the U.S., don’t pay for global rights.

- Term - Is it for one year? Forever? Most docs get perpetual rights.

Pro tip: Always ask for a written license agreement. Verbal promises don’t hold up. And never assume a clip is free just because it’s on YouTube or Vimeo. Those platforms don’t own the rights.

Public Domain: The Free Zone

Some footage is completely free to use. In the U.S., works published before 1929 are in the public domain. That includes silent films, early newsreels, and government productions.

But here’s the catch: the film may be public domain, but the copy you found might not be. If a company restored, colorized, or remastered a 1925 film, they might own the rights to that new version. Always trace the source. The Library of Congress and the Internet Archive are your best bets for verified public domain material.

Example: The 1927 film Metropolis entered public domain in the U.S. in 2023. But if you download a 4K remaster from a commercial site, they might still claim rights over their restoration. Stick to the original scans from official archives.

What About Home Movies?

Found a family video from 1962 on a dusty VHS? You think it’s yours-but is it?

Ownership of home movies is murky. If you shot it, you own it. If you found it, you don’t. Even if the person who made it is dead, their heirs might still hold copyright. Unless you have written permission from the estate, don’t use it.

There’s one exception: if the footage was never published and the creator is unknown, it might fall under "orphan works." But U.S. law doesn’t give you legal protection for using orphan works. You’re still at risk.

Best move? Contact the family. Ask for permission. Get it in writing. Even a simple email saying, "I’d like to use this in my documentary, with credit," is enough.

What If You Get a Cease-and-Desist?

Let’s say you used a clip you thought was fair use-and you get a letter from a lawyer. Don’t panic. But don’t ignore it either.

Step one: Stop using the clip. Step two: Consult a lawyer who specializes in media law. Don’t rely on Reddit advice. Step three: If you truly believe it’s fair use, your lawyer can send a counter-notice. But that can lead to a lawsuit.

Most indie filmmakers settle. Why? Legal fees can cost $10,000+. A license for the clip might be $2,000. It’s cheaper to pay than to fight.

Documentaries like The Fog of War and 13th spent tens of thousands on licensing. They knew the cost of legal trouble wasn’t worth it.

Real-World Checklist for Archival Footage

Before you use any old video, ask yourself:

- Is this footage under copyright? (Check the year and source)

- Am I using it for commentary, critique, or education? Or just to fill space?

- How much am I using? Is it the most important part?

- Could this replace the original? Would someone buy this clip because they saw it in my film?

- Do I have a written license? Or written permission from the rights holder?

- If I’m using public domain footage, is it the original version-or a restored copy?

- Have I documented my fair use reasoning? (Write it down. It helps if you’re challenged.)

If you answer "no" to any of these, don’t use it. Find another clip. Or pay for it.

Bottom Line: Don’t Guess. Document.

Archival footage is powerful. It connects your story to real history. But using it without due diligence is like driving without a seatbelt. You might get away with it-but one crash, and you lose everything.

For every clip you want to use, write down:

- Where you found it

- Who owns it

- Why you think it’s fair use (or how you licensed it)

- How much you’re using

- Whether you got permission

Keep that file. If you ever get questioned, you’ll have proof you tried to do the right thing. That’s not just legal protection-it’s professional integrity.

Can I use archival footage from YouTube in my documentary?

No-not unless you have permission from the copyright owner. YouTube users don’t own the rights to most videos they upload. Even if the video is old or has no copyright notice, it’s still protected. Using it without permission puts you at legal risk. Always track down the original source and verify ownership.

Is all government footage free to use?

Most U.S. federal government footage is in the public domain, especially from agencies like NASA, the National Archives, or the Department of Defense. But state and local government footage may still be copyrighted. Always check the source. The Library of Congress and archives.gov are reliable places to find verified public domain material.

How much does it cost to license archival footage?

Costs vary widely. Short clips from news archives like AP or Getty can start at $300-$800 for non-commercial use. Broadcast rights for a 10-second clip might cost $2,000-$5,000. For major historical footage used in a wide-release documentary, fees can go up to $20,000 or more. Always negotiate based on your budget and intended distribution.

What if I can’t find the copyright owner?

That’s called an "orphan work." U.S. law doesn’t give you legal protection to use orphan works, even if you’ve made a good-faith effort to find the owner. The safest route is to avoid using it. Look for alternatives in public domain archives or consider re-creating the scene with new footage.

Can I use music with archival footage without a license?

No. Music is a separate copyright from the video. Even if the footage is public domain, the soundtrack may still be protected. Using a 1950s news clip with its original background music requires a license for the audio. Always clear music rights separately-or replace it with royalty-free music.

Comments(10)