When you review a movie, you talk about the acting, the score, the pacing, the visuals. But what if you never mentioned whether the film could actually be watched by someone who is deaf, hard of hearing, or blind? That’s not just an oversight-it’s a blind spot in the review itself.

Accessibility isn’t a bonus. It’s part of the film.

A movie isn’t just what you see on screen. It’s what you hear, what you read, and how clearly you can follow the story. Subtitles, captions, and audio description aren’t afterthoughts added for legal compliance. They’re essential parts of the storytelling experience. If a film uses sound design to build tension-like the distant hum of a refrigerator in a horror scene-or relies on visual cues to convey emotion, and those aren’t accessible, then the film isn’t fully realized for half its potential audience.

Think about it: if a reviewer praises a film’s cinematography but doesn’t mention whether the audio description accurately captures the protagonist’s trembling hands or the flicker of a candle in a dark room, they’re only telling half the story. The same goes for a dialogue-heavy drama where subtitles are poorly timed or missing key sound effects. That’s not just bad accessibility-it’s bad criticism.

What’s actually in the movie? Not just the script.

Subtitles and captions do more than translate spoken words. They convey environmental sounds: a door slamming, glass breaking, footsteps on gravel. In Sound of Metal, the gradual loss of hearing isn’t just a plot point-it’s the entire emotional core. If the subtitles don’t indicate when music fades out or when silence becomes the dominant sound, the review misses the point entirely.

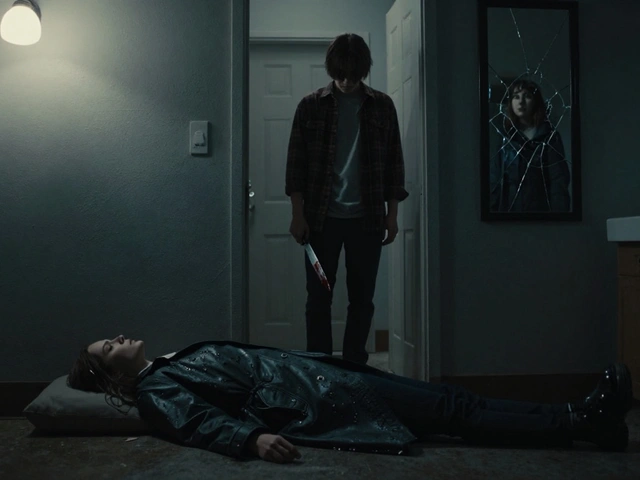

Audio description (AD) is even more overlooked. It’s the spoken narration that describes key visual elements during pauses in dialogue. A good AD doesn’t just say, “The man walks into the room.” It says, “The man walks into the dimly lit room, his face shadowed, eyes wide with fear, as a single red light blinks on the wall behind him.” That’s not fluff. That’s context. And if a reviewer doesn’t note whether the audio description is clear, accurate, and emotionally resonant, they’re not evaluating the film-they’re evaluating a version of it.

Why do most reviews ignore this?

It’s not that reviewers don’t care. It’s that most haven’t been trained to look for it. Film criticism has long been built around the assumption that the viewer has full sensory access. That’s outdated. Nearly 15% of U.S. adults have some form of hearing loss. Over 10 million are blind or have low vision. That’s not a niche audience-it’s a massive one.

And yet, out of the top 100 film reviews on major sites in 2025, only 12 mentioned accessibility features at all. And of those, only four gave any real detail. Most just said, “Subtitles available.” That’s like saying a car has wheels and calling it a review.

There’s also a cultural blind spot. Accessibility is often treated as a technical feature, not an artistic one. But it’s not. Audio description is written by professionals who study pacing, tone, and emotional beats. Captions are timed with the rhythm of the scene. These are creative choices-and they deserve critical attention.

How to review accessibility like a pro

Here’s how to make accessibility part of your review process:

- Watch with accessibility enabled. Don’t assume it’s there. Turn on captions and audio description from the start. See how they integrate-or clash-with the film.

- Check accuracy. Are sound effects described correctly? Are names spelled right? Is the emotional tone of the narration matching the scene? In Oppenheimer, a weak AD might just say, “A crowd reacts.” A strong one says, “The crowd gasps as the first nuclear blast lights up the desert, their faces frozen in terror.”

- Assess timing. Does the audio description interrupt dialogue? Are captions delayed? Poor timing can ruin immersion. In Barbie, if the AD doesn’t catch the exact moment Barbie’s smile cracks, you lose the emotional shift.

- Compare versions. If the film has multiple subtitle options (e.g., SDH vs. plain), note the difference. SDH (Subtitles for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing) includes sound cues. Plain subtitles don’t. That matters.

- Ask: Could someone fully experience this without seeing or hearing the screen? If the answer is no, say why.

What good accessibility looks like

Some films get it right. Everything Everywhere All at Once used audio description to emphasize the chaos of multiverse transitions-describing swirling colors, shifting textures, and the weight of each universe collapse. The AD didn’t just describe; it amplified the film’s emotional overload.

The Whale used captions to mirror the protagonist’s muffled hearing, fading out background noise during his panic attacks. That wasn’t a technical choice-it was a narrative one. And reviewers who missed it missed the film’s deepest layer.

On the flip side, John Wick: Chapter 4 had a well-produced action film but its audio description was robotic. It said, “Gunfire,” instead of, “Rapid gunfire echoes off marble walls as bullets ricochet around the ballroom, shattering chandeliers.” That’s not just lazy-it’s disrespectful to the film’s artistry.

Accessibility as a rating factor

Should accessibility be part of your star rating? Yes. Not because it’s a checklist item, but because it reflects the film’s inclusivity and respect for its audience.

Think of it this way: a film can have perfect acting, stunning visuals, and a brilliant script-but if you can’t follow it because the captions are missing key sounds or the audio description skips emotional beats, then the film fails its audience. That’s a flaw. And flaws deserve to be noted.

Some reviewers now include a separate accessibility score. Others weave it into their overall assessment. Either way, the standard is changing. Audiences are demanding it. Studios are investing in it. Critics need to catch up.

The future of film reviews is inclusive

By 2026, major streaming platforms will be required to provide full audio description and captioning for 100% of their original content under new FCC guidelines. Netflix, Disney+, and Amazon already do. So do most theaters in major cities.

But if reviewers keep ignoring accessibility, those efforts stay invisible. And if they stay invisible, studios won’t prioritize quality. They’ll just check the box.

Good accessibility isn’t about compliance. It’s about care. It’s about saying, “This story matters to everyone.” And if you’re writing a review, you’re not just judging the film-you’re judging how well it reaches the world.

Next time you watch something, turn on the captions. Put on the audio description. See what you’ve been missing. Then write about it. Not as an afterthought. As part of the story.

Are subtitles and captions the same thing?

No. Subtitles are primarily for dialogue translation or when sound is muted. Captions, especially SDH (Subtitles for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing), include dialogue, sound effects, music cues, and speaker identification. For example, "[sirens wailing]" or "[laughter from off-screen]" are captions, not subtitles.

What is audio description, and who uses it?

Audio description (AD) is a narrated track that describes key visual elements during pauses in dialogue. It’s used by people who are blind or have low vision. A good AD doesn’t just say what’s happening-it conveys emotion, movement, and context. For example: "The child clutches her stuffed bear, tears streaming as the door slams shut behind her."

Do all streaming services offer good audio description?

No. Quality varies widely. Netflix and Disney+ generally have strong AD with trained narrators and detailed descriptions. Some smaller platforms or older films have robotic, generic, or incomplete descriptions. Always test it. Look for descriptions that match the film’s tone and pacing-not just factual statements.

Can I request better accessibility features for a film?

Yes. If a film you love has poor or missing audio description or captions, contact the studio or distributor. Many have accessibility feedback forms. Public pressure has led to improved AD for films like Avatar: The Way of Water and The Marvels after fan campaigns. Your voice matters.

Why should I care about accessibility if I don’t need it?

Because film is a shared cultural experience. If you care about storytelling, you care about who gets to experience it. Accessibility isn’t charity-it’s equity. And when you review a film, you’re not just speaking for yourself. You’re speaking for the audience. Ignoring accessibility means ignoring part of that audience. That’s not just incomplete-it’s unfair.

Next time you sit down to write a review, ask yourself: Did this film speak to everyone? Or just some?

Comments(6)