When a VFX-heavy film hits its final edit, the work isn’t done. In fact, the most critical phase is just beginning: the final pixel check. This isn’t about fixing a blown-out sky or tweaking a dragon’s scale. It’s about catching the tiny errors that slip through weeks of rendering, compositing, and review cycles - the kind that only show up on a 4K cinema projector in a dark room, or on a 65-inch TV at 3 a.m. in a producer’s living room.

Every frame of a modern blockbuster contains hundreds of layered elements: CGI characters, digital environments, particle effects, motion blur, lens flares, and more. One misplaced shadow, a texture that doesn’t tile correctly, a reflection that doesn’t match the lighting - these don’t break the story, but they break immersion. And in today’s hyper-aware audience, that’s enough to pull viewers out of the movie.

What Exactly Is a Final Pixel Check?

A final pixel check is a frame-by-frame, pixel-level review of every visual effect in the finished cut. It’s done after color grading, sound mixing, and editorial lock. No more changes to the timeline. No more reshoots. Just pure inspection: is every pixel where it should be?

This step is handled by a small team - often just two or three senior VFX supervisors and a lead QA artist. They don’t look at the whole shot. They zoom in. They scrub frame by frame. They use tools like Nuke, Maya, and custom scripts that flag anomalies: motion artifacts, edge ringing, chromatic aberration, flickering alpha channels, or mismatched grain.

For example, in Avatar: The Way of Water, the team ran over 120,000 individual pixel checks on just the underwater sequences. Why? Because every bubble, ripple, and light refraction had to behave exactly like real water - and any glitch in the simulation would look like a mistake, not magic.

Common Pixel-Level Errors That Get Missed Until the End

Most VFX errors are caught early. But some hide in plain sight. Here are the top five that slip through:

- Edge feathering mismatch - A character’s hair or fur blends too smoothly into the background in one shot, but not the next. The difference is barely visible on a laptop, but glaring on a cinema screen.

- Reflection inconsistency - A CGI car reflects the sky in one shot, but in the next, it reflects nothing. Why? The environment map wasn’t updated after a lighting change.

- Particle pop-in - Smoke or dust particles appear suddenly instead of fading in. Happens when render resolution doesn’t match compositing resolution.

- Alpha channel leakage - A character’s transparent cloak shows a faint halo of background color. Only visible when the shot is slowed down or viewed in high contrast.

- Temporal flicker - A digital flame flickers at 23.976 fps but the source plate was shot at 48 fps. The mismatch creates a strobing effect that’s invisible at normal speed but ruins slow-motion scenes.

These aren’t bugs. They’re artifacts. And they’re almost always caused by a disconnect between departments - compositing didn’t know the render resolution changed, the lighting team didn’t update the reflection map, the editor cut a frame without re-rendering the VFX.

The Tools That Make Pixel Checks Possible

You can’t do this by eye alone. Even the most experienced artist misses things after 10 hours of staring at screens. That’s why studios use automated tools alongside human review.

Frame.io and ShotGrid now integrate with custom pixel-diff scripts that compare each VFX shot against its reference plate. These scripts flag:

- Pixel deviation above 0.5% in luminance or color

- Changes in edge sharpness beyond 1.2 pixels

- Unintended transparency in areas marked as opaque

- Frame-to-frame motion inconsistencies in particle systems

But automation only gets you halfway. The real magic happens when a human sits down with a 4K monitor, a calibrated colorimeter, and a checklist. They watch the entire reel in sequence - not shot by shot, but as a continuous experience. That’s when they catch things like: “The dragon’s wing shadow in scene 47 doesn’t match the weight of the shadow in scene 49. The lighting artist changed the sun angle, but forgot to update the shadow map.”

Who’s Responsible? The VFX Pipeline Breakdown

There’s a myth that VFX quality control is the job of the VFX studio. It’s not. It’s a shared responsibility across the entire production chain.

- Editor - Must flag any cut that removes or shortens a VFX shot without re-rendering. A 2-frame cut can break a 300-frame simulation.

- Colorist - Must ensure VFX elements respond to grading the same way as live-action. A shot that looks fine in log space can turn neon green after LUT application.

- Production VFX Supervisor - Owns the final look. They sign off only after the pixel check is complete and all flagged issues are resolved.

- Post-Production QA Team - The unsung heroes. They run automated scans, log errors, and coordinate fixes. They don’t create effects - they prevent them from breaking.

On Stranger Things Season 4, a single pixel error in the Upside Down’s flickering lights caused a 72-hour delay. The issue? A VFX artist used a different gamma setting in their render farm than the one used in the final grading suite. The lights looked fine on their monitor. On the studio’s 4K projector, they pulsed visibly - like a bad neon sign.

How to Run Your Own Final Pixel Check

If you’re working on a smaller project - indie film, commercial, or short - here’s a simple workflow that works:

- Export the final cut as a 10-bit ProRes 4444 file with alpha channels preserved.

- Use DaVinci Resolve’s “Frame Comparison” tool to overlay each VFX shot against its original plate. Look for shifts in alignment, brightness, or color.

- Play the entire reel on a calibrated 4K monitor. Turn off all lights. Watch it once at normal speed, then once in slow motion.

- Pause every 10 seconds. Zoom to 200%. Look at edges, reflections, and transitions.

- Use a free tool like PixelCheck (open-source) to scan for alpha leaks or color banding.

- Have a second person review. One person sees motion. The other sees color. Two eyes catch twice as much.

Don’t skip the slow-motion pass. That’s where 80% of temporal errors hide.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

Streaming platforms now demand 4K HDR delivery. Audiences watch on OLED TVs with perfect black levels. Every imperfection is amplified. A VFX studio might deliver a shot that looks great on a phone - but on a 77-inch LG G3, the same shot reveals a texture seam, a color shift, or a flickering reflection.

Netflix’s VFX guidelines now require studios to submit a “Final Pixel Report” - a document listing every flagged issue and its resolution status. If you don’t submit it, your project gets rejected. No exceptions.

This isn’t about perfection. It’s about consistency. The audience doesn’t notice the perfect VFX. They notice the ones that don’t belong.

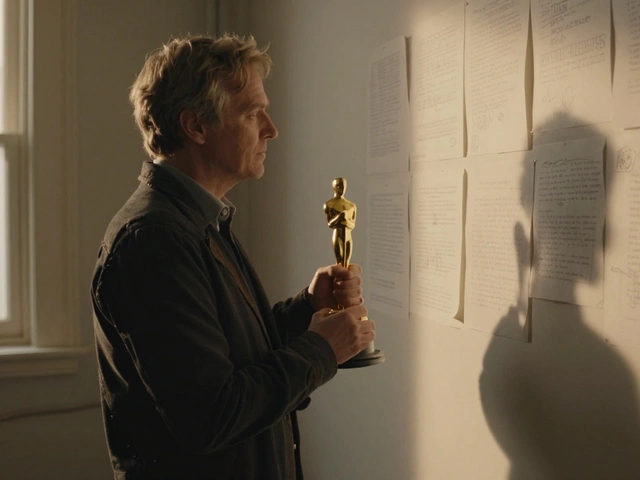

Real-World Example: The $2 Million Mistake

In 2023, a major studio spent $2 million on a CGI creature for a summer blockbuster. The creature looked flawless in dailies. The director loved it. The final render passed internal review.

Then came the pixel check.

One frame - just one - showed the creature’s tail flicking through a wall. The wall was supposed to be solid. The tail was supposed to be behind it. But because the depth buffer wasn’t updated after a last-minute camera move, the tail rendered in front. It lasted 0.12 seconds.

The studio had to re-render 147 shots. The release was delayed by three weeks. The cost? Another $1.8 million.

That one frame cost more than the entire budget of many indie films.

Final Thought: Quality Isn’t a Step - It’s a Mindset

Quality control isn’t the last thing you do before delivery. It’s the thing you do every day. Every render. Every comp. Every edit. If you wait until the end to check pixels, you’re already behind.

The best VFX teams build checks into their pipeline: automated alerts for color drift, daily pixel audits, mandatory second reviews for key shots. They don’t wait for the final deadline. They catch problems early - before they become expensive.

But even the best pipelines miss things. That’s why the final pixel check still exists. It’s not a formality. It’s the last line of defense. And in a world where audiences notice everything, it’s the only thing standing between a masterpiece and a glitch.

What is the difference between a VFX review and a final pixel check?

A VFX review happens during production and focuses on creative choices: Does the dragon look scary? Does the explosion feel big enough? A final pixel check happens after everything is locked and focuses only on technical accuracy: Is every pixel in the right place? Are there any artifacts, leaks, or mismatches?

Can I skip the final pixel check if I’m on a tight budget?

You can, but you’re risking your entire project. Even low-budget films now stream on 4K devices. A single pixel error - like a flickering reflection or a color shift - can make your work look amateurish. It’s cheaper to spend 8 hours on a pixel check than to deal with negative reviews, platform rejections, or having to re-render everything later.

What software do professionals use for pixel checks?

Most studios use Nuke for compositing and frame comparison, DaVinci Resolve for color and edge analysis, and custom Python scripts to automate anomaly detection. Free tools like PixelCheck and VFX Checker can help indie creators run basic scans. The key isn’t the tool - it’s the process. Zoom in. Scrub frame by frame. Watch in silence.

How long should a final pixel check take?

For a 90-minute film with 800 VFX shots, expect 5-10 days. For a 20-minute short with 100 shots, plan for 1-2 days. Speed isn’t the goal - thoroughness is. Rushing this step leads to costly fixes later. Most studios assign two people: one to watch motion and timing, another to watch color and edges.

Do streaming platforms like Netflix or Disney+ require pixel check reports?

Yes. Netflix requires a Final Pixel Report as part of their delivery specs. Disney+ and Amazon Prime Video have similar requirements. These reports list every flagged issue and its resolution. If you don’t submit one, your project won’t be approved - no matter how good the story is.

Comments(10)