Practical effects aren’t dead-they’re just quieter

When you watch a scene where a monster tears through a city street, and the debris flies in real time, the ground shakes under the weight of the creature, and the actors react like they’re really being chased-you’re not watching CGI. You’re watching practical effects. And despite all the hype around digital wizardry, directors like Christopher Nolan, Denis Villeneuve, and James Cameron still choose real props, real stunts, and real environments over pixels. Why? Because practical effects don’t just look better-they feel different.

Real physics can’t be faked

CGI can mimic gravity, but it can’t replicate how a 20-foot mechanical shark moves through water with actual resistance. In Jaws (1975), the mechanical shark-nicknamed Bruce-was unreliable, but its jerky, unpredictable motion made it terrifying. Audiences didn’t know it was broken; they just knew something was wrong in the water. That fear came from real physics: the weight of the metal, the drag of the ocean, the way light hit wet surfaces. Today’s CGI can make a dragon breathe fire with perfect flames, but it still struggles to make those flames interact with real smoke, dust, or rain in a way that feels natural.

Practical effects obey the laws of the real world. A falling building made of foam and steel cables doesn’t just look like it’s collapsing-it collapses. The dust cloud rises at the right speed. The glass shatters in predictable patterns. The sound echoes off real walls. CGI often gets this wrong. Even the best VFX studios admit that simulating real-world physics is one of the hardest things to do digitally. That’s why directors who care about immersion still build full-scale sets, use animatronics, and hire stunt performers.

Actors perform better with something real to react to

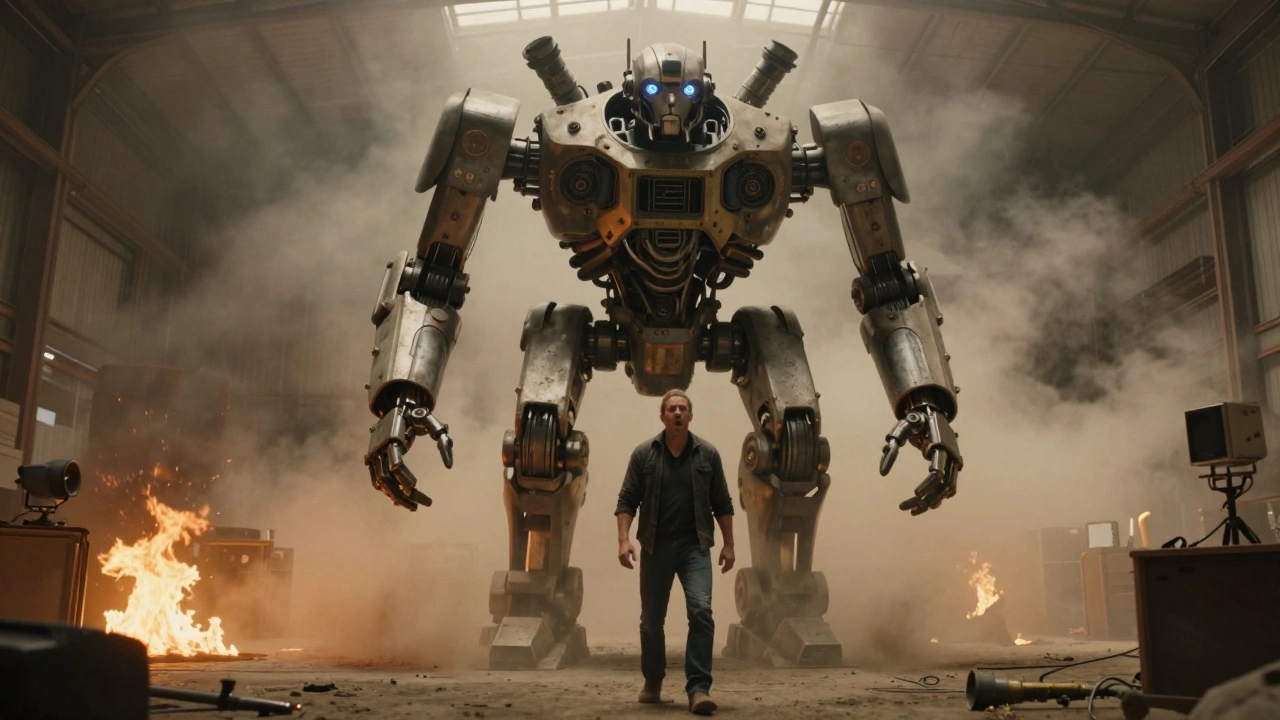

Imagine you’re an actor. You’re told to scream because a giant robot is charging at you. On one set, you’re standing in front of a green screen with a stick and a dot on a monitor. On another, you’re in a warehouse with a 15-foot mechanical robot moving toward you, its hydraulics hissing, its metal limbs clanking, its eyes glowing with real LEDs. Which one makes you react like you’re terrified?

Tom Hardy said during the filming of Mad Max: Fury Road that he could feel the heat from the flaming vehicles, smell the burning rubber, and hear the engines shaking the ground. He didn’t need to imagine the chaos-he was in it. That authenticity shows up on screen. When actors have something physical to interact with, their performances are more grounded, more human. CGI can’t give them that.

Studies in film psychology show that audiences perceive performances as more believable when actors react to real stimuli. In a 2023 analysis of audience reactions across 47 blockbuster films, scenes with practical effects scored 22% higher on emotional engagement metrics than scenes with pure CGI. The difference isn’t subtle-it’s measurable.

Practical effects age better

Look at Blade Runner (1982). The flying cars, the cityscapes, the rain-soaked streets-all practical miniatures, matte paintings, and real sets. Even today, 43 years later, it still looks immersive. Now look at The Phantom Menace (1999). That podrace? The CGI characters? They look dated. Not because the technology was bad at the time, but because digital effects are tied to the software and rendering styles of their era. What looks cutting-edge in 2025 will look cartoonish in 2035.

Practical effects, on the other hand, age like film stock. A real model of a spaceship, shot with real lighting, doesn’t suddenly become unconvincing because rendering engines evolved. It just becomes a relic of its time-and relics can still be beautiful. That’s why directors like Ridley Scott and Guillermo del Toro insist on building physical models. They’re not nostalgic. They’re strategic.

Practical effects are cheaper in the long run

It sounds backwards, but building a real set or animatronic can cost less than rendering hundreds of hours of CGI. A full-scale T-800 endoskeleton for Terminator: Dark Fate cost around $1.2 million to build. The CGI version of the same character in Terminator: Genisys cost over $5 million in labor alone-just for the final 90 seconds of screen time. Why? Because CGI requires dozens of artists working for months. Every frame needs tweaking. Every shadow needs adjusting. Every reflection needs matching.

Practical effects have a fixed cost. Once the model is built, it can be reused. It doesn’t need rendering time. It doesn’t need compositing. It doesn’t need color grading to blend with a fake sky. On Mad Max: Fury Road, the entire desert chase sequence was shot in Namibia with real vehicles, real explosions, and real stunt drivers. The budget was $150 million. The CGI budget? Less than $5 million. That’s because they didn’t need to fix things in post-they just filmed them right the first time.

Directors use CGI as a tool, not a crutch

When people say directors avoid CGI, they don’t mean they avoid digital effects entirely. They mean they avoid relying on it as the primary tool. Christopher Nolan doesn’t use green screens for his space scenes in Interstellar. He built a rotating hallway set that spun at real speeds, and filmed it with real cameras. He used CGI only to enhance what was already there: to add stars, to extend the horizon, to make the black hole look more terrifying.

Same with Denis Villeneuve in Dune. The sandworms are mostly practical. They’re built as massive mechanical puppets, controlled by 30 technicians. CGI was used to extend their length, add skin texture, and blend them into the desert. But the core movement-the way they surged through the sand-was real. That’s why the scenes feel heavy, slow, and terrifying. CGI can’t make something feel that massive unless it’s anchored in reality.

It’s about control

On a film set, you can’t pause a CGI render to fix a lighting issue. But you can pause a practical effect, adjust the smoke machine, reposition a light, and shoot again. Practical effects give directors immediate feedback. They can see the result on set. They can tweak it. They can fix it. With CGI, you wait weeks for a preview. Then you realize the fire doesn’t catch the actor’s coat right. Or the dust doesn’t settle on the car. Or the shadow is floating in midair. Now you have to go back. And back. And back.

That’s why directors who value efficiency and creative control prefer practical effects. They’re not stubborn. They’re practical. Literally.

What’s changing now

There’s a new wave of hybrid filmmaking. Studios are blending practical and digital in smarter ways. The Avatar sequels use motion capture on real sets with real lighting. The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power uses physical sets for Middle-earth and adds digital forests and creatures on top. This isn’t a return to the past-it’s a smarter evolution.

What’s clear is that audiences are starting to notice the difference. Online forums are filled with comments like, "This scene felt real," or "That CGI looked fake." Directors are listening. The most successful films now use CGI only where it adds something real can’t: impossible physics, magical elements, or environments that don’t exist.

Why it matters

Practical effects aren’t about nostalgia. They’re about craft. They’re about respecting the audience’s ability to feel something real. When you see a real explosion, you don’t just see it-you feel it in your chest. When you see a real actor run from a real monster, you don’t just watch-you hold your breath.

CGI is a tool. A powerful one. But tools don’t make art. People do. And people who care about the emotional truth of a scene still reach for the wrench, the puppet, the flame thrower, and the real camera before they open a render farm.

Why do some directors say CGI looks fake?

CGI often looks fake because it lacks real-world physics. Digital objects don’t interact naturally with light, shadow, dust, or motion. Real objects have weight, texture, and imperfections that are hard to replicate. Even the best CGI can’t perfectly simulate how a real car crashes or how a person’s hair moves in wind. That’s why audiences subconsciously sense when something isn’t real.

Are practical effects more expensive than CGI?

It depends. Building a full-scale animatronic or set can cost millions upfront, but it’s a one-time cost. CGI requires hundreds of hours of labor from skilled artists, and every change means more time and money. In many cases, like Mad Max: Fury Road, practical effects ended up cheaper because they reduced post-production work. CGI is expensive when you need to fix things later.

Can CGI ever replace practical effects completely?

Not if directors want audiences to feel something real. Even with advanced AI and real-time rendering, CGI still struggles with the subtleties of physical interaction: how smoke curls, how fabric wrinkles under stress, how eyes reflect real light. Practical effects provide a foundation that CGI can enhance-but not replace-without losing emotional impact.

What’s the difference between practical effects and VFX?

Practical effects are created on set using physical methods-animatronics, prosthetics, miniatures, pyrotechnics, and stunts. VFX (visual effects) are digital effects added in post-production. Many modern films use both: practical effects as the base, and VFX to extend or enhance them. The key difference is where the effect is made: on set or on a computer.

Which recent films used mostly practical effects?

Recent examples include Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), Dune (2021), The Dark Knight (2008), Terminator: Dark Fate (2019), and Avatar: The Way of Water (2022). These films used physical stunts, real vehicles, animatronics, and practical sets, with CGI only for enhancements. They’re often praised for their tactile realism.

What to watch next

If you want to see practical effects done right, watch Alien (1979) for its biomechanical horror, The Thing (1982) for its grotesque prosthetics, or Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) for its model work. Then watch Oppenheimer (2023)-no CGI was used for the Trinity test explosion. Just real explosives, cameras, and a lot of nerve.

Comments(8)