Most new screenwriters skip the outline. They jump straight into writing dialogue, hoping the story will magically come together. It rarely does. A strong screenplay doesn’t start with great lines-it starts with a clear structure. The difference between a script that gets read and one that gets tossed? A solid outline. You don’t need to be a genius. You just need to know how to build from a single sentence to a full beat sheet.

Start with the logline

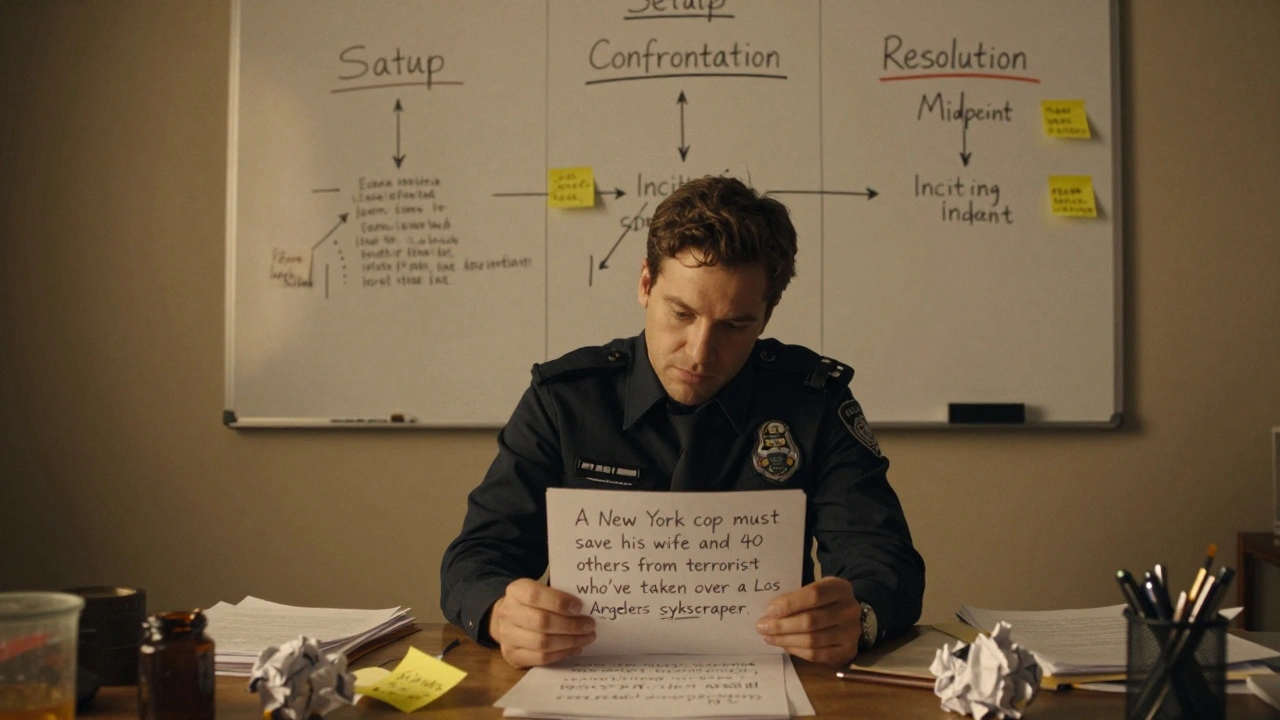

Your logline isn’t a fancy pitch. It’s the one-sentence engine of your whole script. If you can’t say it in one sentence, you don’t know your story yet. A good logline includes three things: the main character, their goal, and the main obstacle. And it has to sound like something you’d say out loud.Take Die Hard: "A New York cop must save his wife and 40 others from terrorists who’ve taken over a Los Angeles skyscraper." That’s it. No fluff. No metaphors. Just who, what, and why it’s hard.

Write five versions of your logline. Cross out the weak ones. Keep the one that makes you want to see the movie. If your logline sounds like a movie you’ve already seen, change the obstacle. If it’s too vague-"a man tries to find himself"-add specifics. Who is he? What does he want? What’s stopping him?

Break the story into three acts

Every great film follows a three-act structure. It’s not a rule. It’s a pattern that works because it matches how humans experience stories.Act One: Setup. You meet the character. You see their world. Something happens that forces them out of it. That’s the inciting incident. It’s not the climax. It’s the first domino.

Act Two: Confrontation. The character tries to solve their problem. They fail. They get pushed harder. They change. This is where most scripts drag-because writers don’t raise the stakes. Every scene here should make things worse before they get better.

Act Three: Resolution. The character faces their biggest challenge. They use what they’ve learned. The story ends. Not with a bang, but with a shift. The character is not the same person they were at the start.

Think of it like a rollercoaster. Act One is the climb. Act Two is the drops and loops. Act Three is the slow return to the station-with your heart pounding.

Build the 15-beat sheet

Once you have your three acts, break them into 15 key moments-the beats. These aren’t scenes. They’re turning points. Each beat moves the story forward and changes the character’s path.Here’s the standard 15-beat structure used by studios and working screenwriters:

- Opening Image - What does the world look like before the story starts? A quiet office. A broken marriage. A lonely spaceship.

- Theme Stated - Someone says the theme out loud. "You don’t have to be perfect to be worthy." It’s often said by a side character.

- Set-Up - Show the character’s normal life. Their habits, flaws, relationships. This is where you plant the seeds for their change.

- Inciting Incident - The event that shatters their normal world. A letter arrives. A phone call. A stranger walks in.

- Debate - The character hesitates. Should they take the risk? They talk to friends. They make excuses. This isn’t just doubt-it’s resistance.

- Break into Two - They make the choice. They cross the threshold. No turning back. The story shifts from Act One to Act Two.

- B Story - A secondary plot, usually about relationships. A love interest. A mentor. A sibling. This is where the theme gets explored emotionally.

- Fun and Games - The promise of the premise. If it’s a heist movie, this is where the plan unfolds. If it’s a comedy, this is where the awkward situations pile up.

- Midpoint - A major shift. Either a false victory or a false defeat. The character thinks they’ve won… or they’ve lost everything. The stakes rise.

- Bad Guys Close In - Outside pressure builds. Allies turn. Secrets come out. The character is isolated. This is where the script gets tense.

- All Is Lost - The darkest moment. The character hits bottom. Their plan fails. Their partner leaves. They lose hope. This is not the climax. It’s the moment before the climb.

- Dark Night of the Soul - They sit in the ashes. They reflect. They realize what they need to change. This is where the theme comes home.

- Break into Three - They make a new choice. They find the courage. They’re not the same person anymore. This is the pivot to Act Three.

- Finale - The final confrontation. They face the main obstacle with their new understanding. The stakes are life or death-emotionally or physically.

- Final Image - What does the world look like now? It should mirror the opening image, but changed. The character is different. The world is different.

Fill out each beat with one or two lines. Don’t write scenes yet. Just state what happens. For example: "Midpoint: She finds the hidden file-but it proves her boss is innocent. Now she’s the villain." That’s enough. You’re building the skeleton, not the skin.

Use the beat sheet to write scenes

Now that you have your 15 beats, turn each one into a scene. Don’t write dialogue yet. Write the purpose of the scene. What’s the character trying to achieve? What’s the obstacle? What changes by the end?Every scene must do one of two things: advance the plot or reveal character. If it doesn’t do both, cut it. A scene where two people talk about the weather? Unless that weather is about to kill them, it’s filler.

Use the beats as your checklist. If your scene doesn’t connect to a beat, you’re off track. If two scenes serve the same beat, merge them. If a beat feels empty, ask: What’s the emotional shift here? What does the character learn?

Example: Your Beat 7 is "B Story: The protagonist reconnects with their estranged brother." Your scene isn’t "They have coffee." It’s "They argue over their father’s will-then the brother admits he’s dying. The protagonist realizes he’s been running from grief, not his brother."

Test your outline

Before you write a single line of dialogue, test your outline. Read your 15 beats out loud. Can you follow the story? Does it feel like a movie? Do you care what happens next?Ask yourself:

- Is the protagonist active? Are they driving the story, or just reacting?

- Is the antagonist strong? Do they have clear goals that clash with the hero’s?

- Does the theme show up in action, not just dialogue?

- Is there a moment where the character changes? Not just learns-changes.

- Does the ending feel earned? Or did you cheat to make it work?

If you can’t answer these with confidence, go back. Fix the beats. Add a new obstacle. Strengthen the character’s flaw. Don’t rush to the script. A weak outline becomes a weak script.

Common mistakes to avoid

- Too many beats - Don’t turn this into a 50-point outline. You’re not writing a novel. Keep it tight.

- Skipping the midpoint - This is where most scripts collapse. The story needs a pivot. Without it, Act Two feels flat.

- Confusing plot with theme - The plot is what happens. The theme is what it means. Don’t make the character say the theme. Show it.

- Writing scenes that don’t connect - Every scene must link to a beat. If it doesn’t, delete it.

- Waiting for inspiration - You don’t wait for the muse. You build the structure, and the story comes to life inside it.

Tools to help

You don’t need fancy software. But these free tools help:- Scrivener - Organize beats, scenes, and notes in one place.

- Final Draft - Has built-in beat sheet templates.

- Google Sheets - Make your own 15-beat table. Copy-paste it into every project.

- Notion - Create a template with dropdowns for character arcs and emotional shifts.

Some writers still use index cards. That’s fine. The tool doesn’t matter. What matters is that you write down the beats. And stick to them.

What comes next

Once your beat sheet is solid, you’re ready to write the first draft. But don’t stop there. After the draft, go back to your beats. Did the story follow them? Did you stray? Did you discover something better? Revise the outline to match the script. Outlining isn’t a one-time task. It’s a living framework.Every great screenplay was outlined-often dozens of times. The difference between amateur and professional isn’t talent. It’s discipline. You don’t write a great script by accident. You build it, beat by beat.

Do I have to follow the 15-beat structure exactly?

No. The 15-beat structure is a guide, not a rule. Many successful films bend or skip beats. But if you’re new to screenwriting, follow it exactly until you understand why each beat exists. Once you’ve mastered the pattern, you can break it intentionally-not because you’re confused, but because you know what you’re doing.

How long should my outline be?

One page for the logline and three-act breakdown. Two to three pages for the 15-beat sheet. That’s it. If it’s longer than five pages, you’re overthinking. The outline’s job is to guide, not replace the script.

Can I outline a comedy or horror the same way?

Yes. The structure works for every genre. A horror film’s "All Is Lost" beat might be the character realizing the monster is in the house with them. A comedy’s "Midpoint" might be the fake relationship turning real. The beats stay the same. The tone changes.

What if my story doesn’t fit into three acts?

Stories that don’t fit three acts usually don’t have a clear character arc. Ask: Who changes? How? If no one changes, you don’t have a story-you have a series of events. Even experimental films like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind follow the three-act structure. The beats are just hidden under non-linear storytelling.

How do I know when my outline is done?

When you can read it and feel the movie. When you can’t wait to write it. When you know exactly what the hero wants, what’s stopping them, and how they’ll change. If you’re still guessing, keep working. A great outline doesn’t feel like work-it feels like momentum.

Comments(9)