Why Some Directors Stick to One Genre

Not every director tries to make every kind of movie. Some spend their whole careers inside one genre-horror, westerns, sci-fi, rom-coms-and become the go-to names when studios need someone who gets it. Why? Because audiences trust them. Studios bet on them. And sometimes, the director themselves can’t imagine telling stories any other way.

Take John Carpenter. He didn’t just make horror films-he built the sound, the pacing, the dread of 1980s horror with John Carpenter. His low-budget Halloween didn’t just launch a franchise; it rewrote how fear works on screen. No jump scares overkill. Just silence, a mask, and a sense that evil is always watching. That’s not luck. That’s mastery.

Same with Christopher Nolan. He didn’t start with space epics. But once he found his groove in high-concept sci-fi with Inception and Interstellar, he leaned in hard. His films now come with expectations: non-linear time, practical effects, Hans Zimmer’s booming score. He didn’t abandon drama-he fused it with physics and philosophy. That’s specialization, not limitation.

How Genre Directors Build Their Signature

Specializing doesn’t mean repeating the same plot. It means mastering a set of rules-and then bending them just enough to feel fresh.

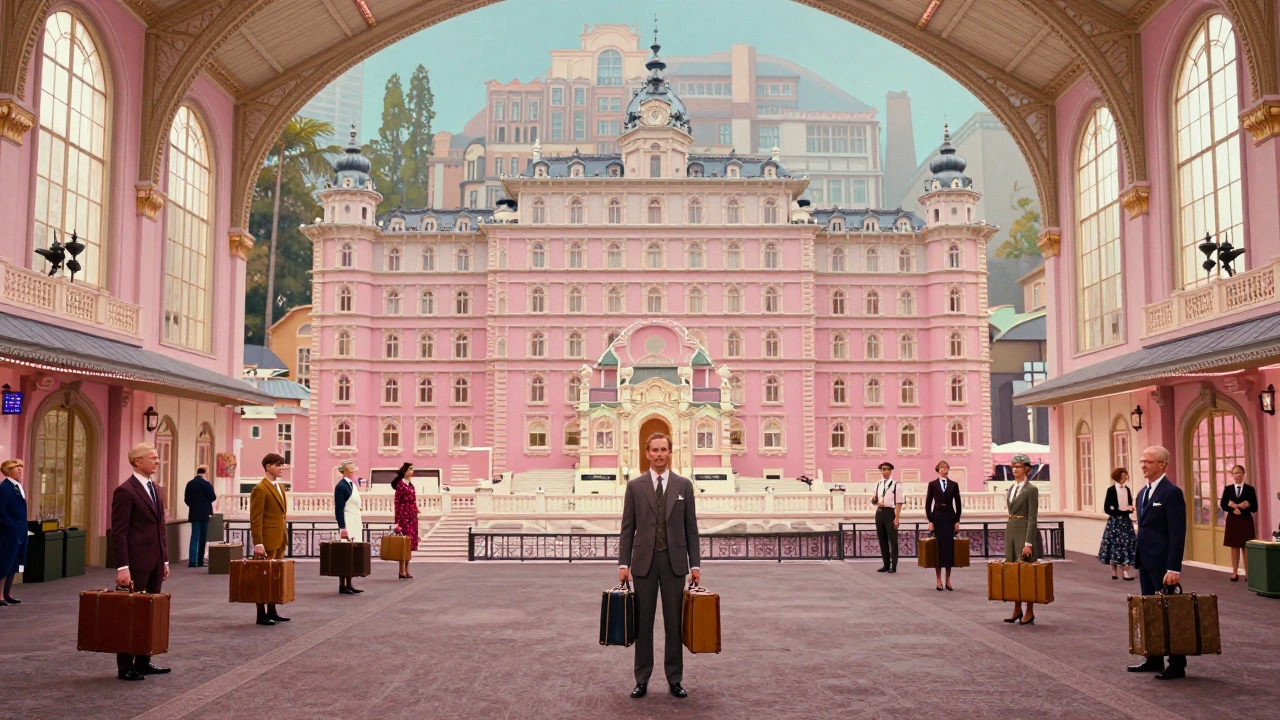

Wes Anderson’s films look like storybooks come to life. Symmetrical shots. Pastel palettes. Deadpan delivery. He doesn’t make ‘quirky’ movies-he makes Wes Anderson movies. Whether it’s The Grand Budapest Hotel or Moonrise Kingdom, you know it’s him before the title card. That’s not a style-it’s a language.

James Wan built his name on horror. Saw brought torture-porn into the mainstream. The Conjuring brought back slow-burn dread. But he didn’t just direct scares-he engineered them. He learned what makes a door creak feel threatening. What lighting turns a hallway into a trap. He turned horror into a formula, then refined it until it became a brand.

These directors don’t just shoot scenes. They design experiences. A horror director doesn’t just show a monster-they make you feel the walls closing in. A romantic comedy director doesn’t just pair two people-they make you believe love could happen in a grocery store line.

Why Studios Rely on Genre Directors

Big studios don’t gamble on unknowns when they have a proven genre specialist. Why spend millions testing a new director on a zombie film when you can hire someone who’s already delivered three hits in that space?

Look at the Evil Dead franchise. Sam Raimi started it in 1981 with a $350,000 budget and a hand-cranked camera. Decades later, the reboot in 2013 still had his DNA: fast zooms, over-the-top gore, dark humor. The studio didn’t need to explain what they wanted-they just said, ‘Make it feel like Raimi.’

Same with Guillermo del Toro. When Netflix wanted a dark fairy tale with monsters that felt real, they didn’t cast a newcomer. They hired del Toro. Why? Because his films-Pan’s Labyrinth, The Shape of Water-don’t just have monsters. They use them to talk about loneliness, war, and love. That’s the kind of depth studios pay for.

Genre directors are risk mitigators. They bring predictability. Not in plot, but in tone, texture, and emotional impact. A studio knows: if you give a horror director $20 million, you’ll get chills-not a confused mess.

What Happens When a Director Switches Genres

Some directors try to break out. And sometimes, it works. Sometimes, it crashes.

David Fincher made his name with dark thrillers: Se7en, Fight Club, Zodiac. Then he made The Social Network-a movie about Facebook. No serial killers. No blood. Just code, ambition, and a brilliant script. It won Oscars. People called it a masterpiece. But here’s the thing: it still felt like Fincher. Cold lighting. Tight pacing. Characters who don’t smile unless they’re lying.

That’s the key. He didn’t abandon his style-he adapted it. He took his signature tension and poured it into a different kind of story.

On the other hand, some directors lose their way. Remember when M. Night Shyamalan tried to move from supernatural thrillers to superhero films with Glass? The fans who loved The Sixth Sense didn’t feel the same magic. The studio didn’t know what to market. Critics called it confused. He wasn’t switching genres-he was trying to be everything at once.

Specialization isn’t about being boxed in. It’s about knowing your voice. When you try to sound like someone else, you lose what made people listen in the first place.

How New Directors Can Find Their Genre

If you’re starting out, don’t try to be Spielberg. Don’t try to be Tarantino. Try to be the person who gets the most excited about one kind of story.

Ask yourself: What movie made you want to direct? Was it the tension in Alien? The rhythm in La La Land? The way Get Out made you laugh and then freeze?

Start small. Make a 10-minute short in your favorite genre. Shoot it on your phone. Cast friends. Use natural light. Don’t worry about budget-worry about feeling. Did you capture the mood? Did the ending land? Did you make someone feel something?

Then do it again. And again. In the same genre. Build a reel that screams, ‘This is what I do.’

By the time you’re ready to pitch a feature, you won’t need to explain your vision. People will already know what you’re capable of.

Genre Directors Are the Unsung Architects of Film

Most people don’t know the names of genre directors. But they know the feeling they leave behind.

When you watch a horror movie and feel your skin crawl, you’re not just scared-you’re experiencing the director’s obsession with dread. When you laugh at a rom-com’s awkward meet-cute, you’re reacting to someone who’s studied human behavior for years.

These directors aren’t just storytellers. They’re cultural translators. They take abstract emotions-fear, hope, longing-and turn them into something you can watch, feel, and remember.

That’s why genre specialization isn’t a limitation. It’s a superpower. The best ones don’t just make movies. They make genres better.

What Makes a Genre Director Legendary?

It’s not how many films they made. It’s how many people remember the feeling.

Alfred Hitchcock never made a fantasy film. But he turned suspense into an art form. His fingerprints are on every thriller made since 1960.

John Woo turned gunfights into ballets. His slow-motion shots of doves flying amid gunfire didn’t just look cool-they made violence feel poetic.

These directors didn’t chase trends. They created them. And they did it by doubling down on what they loved.

That’s the lesson: mastery comes from focus. Not from trying to do everything.

Comments(7)