Independent film production is a high-risk, high-reward game. You’ve got a script, a cast, a vision - but without money, it’s just a file on a hard drive. The biggest question most indie filmmakers face isn’t about lighting or editing. It’s: equity vs debt - which one should you use to fund your movie?

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. But understanding the difference between equity and debt - and how they actually play out on set - can mean the difference between finishing your film and shelving it forever.

What Equity Financing Really Means for Filmmakers

Equity financing means selling a piece of your movie to investors in exchange for cash. They become co-owners. If your film makes money, they get a share. If it flops, they lose their money - and you keep your creative control, mostly.

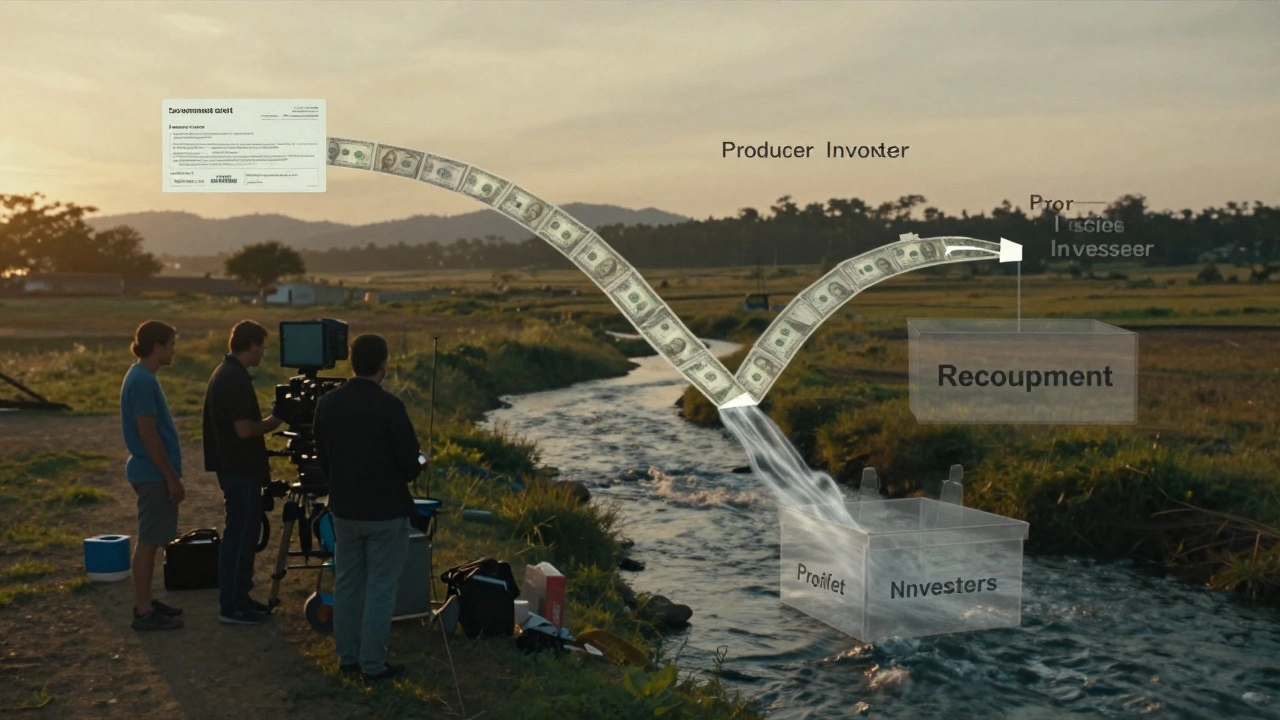

Most indie filmmakers use equity when they can’t qualify for loans. It’s common for producers to raise money from friends, family, or angel investors who believe in the project. A typical deal might give an investor 10-25% of the net profits after recoupment. That means the film has to pay back all production and marketing costs before anyone sees a dime.

Here’s how it works in practice: A filmmaker raises $500,000 from five investors. Each gets 5% of the net profits. The film costs $700,000 to make. It earns $1.2 million in total revenue. After $200,000 in distribution fees and marketing, $1 million is left. The $700,000 production cost is paid back first. The remaining $300,000 is split among the investors and the filmmaker based on their agreed-upon profit share.

Equity doesn’t require monthly payments. That’s the upside. But you’re giving up future earnings. And if your film wins an award or goes viral, those investors could end up making more than you - even if you did 90% of the work.

How Debt Financing Works in Independent Film

Debt financing is borrowing money that must be paid back, usually with interest. Unlike equity, you don’t give up ownership. But you do take on risk - the risk of repayment.

Most indie filmmakers use debt through:

- Production loans from specialized lenders like FilmFinances or Creative Artists Agency (CAA) Finance

- Lines of credit secured by pre-sales or distribution agreements

- Government tax credits used as collateral (common in states like Georgia, Louisiana, and New Mexico)

Let’s say you secure a $400,000 loan at 8% interest over three years. You need to pay back $496,000 total. You can’t start repaying until the film earns money - so lenders often require a lockbox system. That means all revenue from the film goes into a controlled account, and payments are automatically deducted before you see a cent.

Debt is great if you’re confident your film will make money. But if it underperforms? You still owe. And if you can’t pay? The lender can take control of distribution rights, or even force you to sell the film to cover the debt.

Many filmmakers avoid debt because they’ve seen too many projects collapse under repayment pressure. But smart ones use it strategically - like using a tax credit advance to cover 60% of the budget, then using equity for the rest.

When to Choose Equity Over Debt

Equity is the safer bet if:

- You have no proven track record or credit history

- Your film has no pre-sales or distribution deals lined up

- You’re making a low-budget, high-risk project (like a horror film shot in 10 days)

- You’re okay giving up future profits for current cash

Equity investors often bring more than money. They might have connections to festivals, distributors, or press. That’s value you can’t buy. But they also expect involvement. One producer I know had an investor demand to be on set every day - and insisted on changing the ending.

Equity is also the only option if you’re using crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter. Backers aren’t lending money - they’re buying a share of the project. They’re equity in all but name.

When Debt Makes More Sense

Debt is better if:

- You have a solid distribution deal or pre-sale contract

- Your film has a clear path to profitability (e.g., a genre film with a built-in audience)

- You’ve made a film before and have a track record

- You want to keep full creative control and future earnings

Take the 2023 film Little Deaths, shot in rural North Carolina. The producer secured a $350,000 loan backed by a pre-sale to a streaming platform. The film cost $400,000 to make. It earned $1.1 million. After paying back the loan and interest ($420,000), the filmmaker kept $680,000 - all of it. No investors to split with.

That’s the dream. But it only works if you’ve done your homework. Debt lenders don’t care about your passion. They care about your recoupment plan, your cast’s track record, and your distribution strategy.

The Hybrid Model: Mixing Equity and Debt

Most successful indie films use a mix. That’s called a capital stack.

Here’s a realistic breakdown for a $1 million indie film:

| Source | Amount | Type | Repayment Terms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government Tax Credit (advance) | $300,000 | Debt | Repaid from revenue; interest-free |

| Production Loan | $200,000 | Debt | 8% interest, repaid from first revenue |

| Equity Investors | $300,000 | Equity | 20% of net profits after recoupment |

| Producer’s Personal Funds | $100,000 | Equity | 15% of net profits |

| Pre-sale (streaming platform) | $100,000 | Debt | Non-refundable advance, counts toward recoupment |

This structure reduces risk. The producer doesn’t rely on one source. If the pre-sale falls through, the tax credit still covers part of the budget. If the equity investors don’t deliver, the loan still funds production.

The key is balance. Too much debt? You’re drowning in repayment pressure. Too much equity? You’re giving away your future. The sweet spot is usually 40-60% debt, 40-60% equity - depending on your confidence in the film’s returns.

Pitfalls to Avoid

Here’s what goes wrong more often than you think:

- Using equity from unqualified investors who don’t understand film accounting

- Signing debt contracts without understanding the recoupment waterfall

- Assuming tax credits are guaranteed - they’re not, until the state approves them

- Not having a clear profit participation agreement in writing

- Forgetting that distribution fees can eat up 30-50% of revenue

One filmmaker raised $200,000 from friends, promising them 25% of gross revenue. Gross revenue included festival fees and merchandise. When the film only made $150,000 in total, he owed his investors more than the film earned. He had to sell the rights to cover it.

Always get legal advice. Use a film accountant. Don’t trust verbal promises.

What Works in 2025

Today’s indie film landscape is different. Streaming platforms pay less. Theatrical releases are harder to secure. But new tools have emerged:

- Blockchain-based tokenization of film rights (still niche, but growing)

- Revenue-sharing agreements instead of fixed equity splits

- Co-financing with international partners (Canada, UK, Australia)

- Use of AI for budget forecasting and risk modeling

One 2024 film, Still Life in Iowa, used a hybrid model: 50% debt from a Canadian tax credit program, 30% equity from a U.S.-based collective of filmmakers, and 20% from a pre-sale to a niche streaming service. The film broke even in 11 months. The producer kept 70% of the net profits.

The lesson? The right capital mix isn’t about picking equity or debt. It’s about stacking them smartly.

Final Rule of Thumb

Ask yourself this: If your film makes $500,000, would you rather pay back $400,000 in debt - or give away $250,000 in profits?

If you’d rather pay back the loan, go with debt. If you’d rather keep the money and risk losing it all, go with equity.

But the best answer? Use both. Just make sure you know exactly how the money flows - from the investor’s check to the final dollar in your pocket.

Can I use crowdfunding as equity financing?

Yes. Platforms like Kickstarter and Indiegogo let backers contribute in exchange for rewards or profit shares. If backers receive a percentage of future earnings, that’s equity. But if they just get a DVD or credit, it’s a donation - not equity. Always clarify the terms in writing.

Do I need a lawyer to set up equity financing?

Absolutely. Without a proper operating agreement or private placement memorandum, you risk legal trouble. Investors can sue for misrepresentation or breach of contract. A film attorney will help structure profit splits, define recoupment order, and protect your rights.

Can I get a bank loan for a first-time indie film?

Traditional banks rarely lend to first-time filmmakers. But specialized film lenders do - if you have a distribution deal, a strong cast, or a tax credit secured. Your credit score matters less than your recoupment plan.

What happens if my film doesn’t make money?

With equity, investors lose their money - you owe nothing. With debt, you still owe the full amount. That’s why many producers use debt only when they have pre-sales or insurance. Without a safety net, debt can ruin your career.

Are tax credits reliable for financing?

They’re one of the most reliable tools - but only if you file correctly. States like Georgia and Louisiana offer 20-40% cash rebates. But you must spend the money in-state and submit paperwork on time. Many filmmakers lose out because they don’t hire a tax credit specialist.

If you’re planning your next film, don’t just pick the easiest funding source. Map out your options. Run the numbers. Talk to producers who’ve done it before. The right capital mix won’t guarantee success - but the wrong one will guarantee stress.

Comments(6)