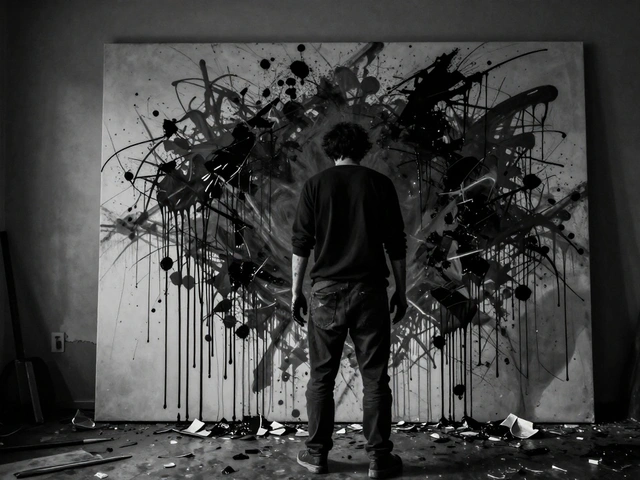

On an indie film set, the difference between a smooth shoot and a meltdown isn’t always the script. More often, it’s how the crew was paid.

Most indie filmmakers start with a dream and a spreadsheet. The dream is great. The spreadsheet? Usually broken. You’ve got $50,000 to make a movie. You need a director, a camera operator, a sound recordist, a gaffer, a production assistant, and maybe a makeup artist. Everyone’s passionate. Everyone’s willing to work for less. But ‘less’ isn’t the same as ‘nothing.’ And when someone shows up to work for 16 hours straight and gets paid $100, they don’t come back. Or worse-they show up angry, tired, and half-hearted.

Here’s the truth: crew rate negotiations on indie films aren’t about squeezing every penny. They’re about building trust. Fair pay keeps people loyal. Unfair pay kills momentum.

What’s a Fair Rate for Indie Film Crew?

There’s no official union scale for indie films under $250,000. That’s the wild west. But that doesn’t mean you make it up as you go.

Look at what’s happening in real indie productions right now. In 2025, a seasoned camera operator on a $100K film in the U.S. typically earns between $300-$500 per day. That’s for a 10-12 hour day. A production assistant? $125-$175. Sound recordist? $350-$600. Gaffer? $400-$700. These aren’t union rates-they’re what working crews in places like Asheville, Atlanta, and Albuquerque are actually accepting for micro-budget films.

Why these numbers? Because crews have been burned too many times. They’ve worked on projects that promised ‘profit participation’ and got nothing. They’ve seen directors who spent $15,000 on a drone but couldn’t pay the key grip $200. Now they ask for cash up front. Or at least a clear payment schedule.

How to Negotiate Without Killing Your Budget

You don’t need to pay market rate. But you do need to pay respectfully.

Start with this: be transparent. Tell your crew exactly how much money you have. Show them your budget breakdown. Don’t hide behind ‘it’s a passion project.’ Passion doesn’t pay rent.

Then, ask: ‘What do you need to feel valued?’ Some people want cash. Others want deferred pay. Some want a producer credit. Others want a meal stipend or travel reimbursement. You don’t have to give everyone everything-but you need to give everyone something real.

Here’s a simple rule: If you can’t pay someone in cash, pay them in equity. Not ‘I’ll give you a credit.’ Not ‘You’ll be in the credits.’ Real equity. A percentage of net profits. And if you’re serious, put it in writing. Even a one-page agreement signed by both sides.

One filmmaker in North Carolina paid her entire crew $100 per day but gave each person 0.5% of net profits. She had a $75,000 film. It made $320,000 on VOD. Everyone got $1,600 extra. No one complained about the daily rate. Because they felt like owners.

Deferred Pay: Use It Wisely

Deferred pay sounds noble. But it’s risky.

Most indie films never turn a profit. If you promise someone $500 a day, deferred, and the film makes $10,000 after festival fees and platform cuts, they get $0. And they know it. So why do they work for you?

Only use deferred pay for roles that are optional. For example: a composer who’s also a friend, or a colorist who’s building their reel. Don’t defer pay for your DP, your AD, or your sound mixer. These are the people who keep the set running. If they’re not paid on time, the shoot collapses.

Here’s a better approach: Pay 50% upfront. Promise the other 50% if the film clears a specific threshold-say, $50,000 in revenue. That gives people skin in the game without leaving them empty-handed.

What to Do When You Can’t Afford Anyone

Let’s say you have $15,000. You need five crew members. That’s $3,000 each. Not enough for a single day’s pay for a DP.

Here’s what works: hire fewer people. Do more with less.

One director in Ohio made a 12-minute film with just three crew: himself (director/camera), a friend (sound and lighting), and a volunteer (production assistant). He used a Sony FX3, a lavalier mic, and natural light. He paid each person $500 upfront. No deferred. No credits. Just cash. The film won three regional awards. Everyone came back for the next one.

Don’t try to hire a full crew if you can’t pay them. It’s not brave. It’s selfish. It’s worse than not making the film at all. Because you’re taking someone’s time, energy, and trust-and giving them nothing.

Instead, simplify. Shoot fewer locations. Reduce the shoot days. Use actors who can also operate cameras. Film on weekends. Get creative with your resources. A lean crew that’s paid well beats a big crew that’s unpaid every time.

What Crew Members Really Want

It’s not about the money alone. It’s about respect.

Ask any crew member who’s worked on five indie films: What made you come back? It wasn’t the free pizza. It was the director who texted them after midnight to say, ‘Thanks for staying late. Here’s $100 extra for gas.’

It was the producer who showed up with coffee at 5 a.m. It was the AD who made sure the lunch truck arrived on time-even when the schedule ran late. It was the editor who got a handwritten note after the premiere.

Money is the baseline. But respect is what turns a crew into a team.

Here’s what you can do without spending a dime:

- Send a thank-you email within 24 hours of each day of shooting.

- Give credit where it’s due-on social media, in press releases, on the film’s website.

- Invite crew to screenings. Buy them a drink. Talk to them like equals.

- Offer to help them with their own projects. Network for them. Introduce them to other filmmakers.

These things cost nothing. But they build loyalty that lasts for years.

The Cost of Cheap Crew

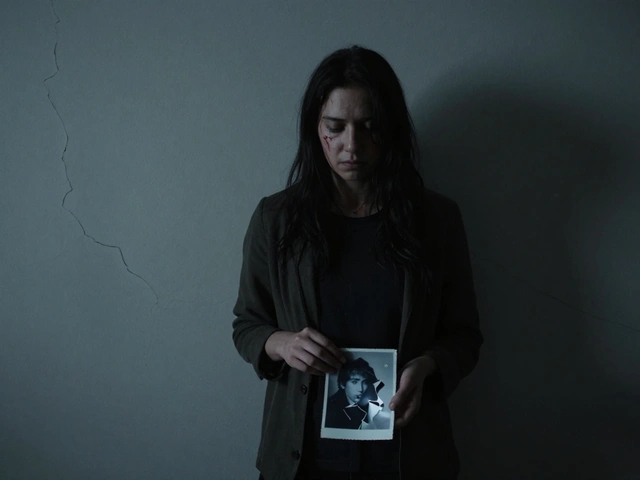

Skipping pay might save you $2,000 now. But here’s what it costs later:

- Your DP quits halfway through because they’re stressed about rent.

- Your sound recordist shows up late because they had to pick up a side job.

- Your editor ghosts you after the rough cut because they’re tired of being taken for granted.

- No one wants to work with you again. Your next film has no crew.

Indie film isn’t a charity. It’s a business. And your crew are your most valuable asset.

Think of it this way: If you were a restaurant owner and your chef worked 14-hour days for free, you’d be seen as a monster. Why is it different when you’re making a movie?

Real Budget Example: ,000 Indie Film

Here’s what a realistic crew budget looks like for a $75,000 film:

| Role | Days | Rate per Day | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Director/Producer | 25 | $150 | $3,750 |

| Director of Photography | 18 | $450 | $8,100 |

| Sound Recordist | 18 | $400 | $7,200 |

| Production Designer | 12 | $300 | $3,600 |

| Key Grip | 15 | $350 | $5,250 |

| Production Assistant (2) | 20 | $150 | $6,000 |

| Editor | 25 | $300 | $7,500 |

| Colorist | 8 | $250 | $2,000 |

| Composer | 10 | $200 | $2,000 |

| Meal Stipends (10 people x 25 days) | - | $15 | $3,750 |

| Travel Reimbursement | - | - | $1,500 |

Total Crew Costs: $41,650

That’s 55% of the budget. It’s not cheap. But it’s realistic. And it leaves room for equipment, insurance, permits, and post-production.

This isn’t a luxury. This is how you make a film people want to watch-and crew want to be part of again.

Final Rule: Pay What You Can, But Never Lie

The worst thing you can do is promise more than you can deliver. Don’t say ‘we’ll pay you after festivals’ if you know you won’t. Don’t say ‘you’ll get a producer credit’ if you’re just trying to get them to work for free.

Be honest. Say: ‘I have $50,000. I can pay you $200 a day. I can’t pay more right now. But I’ll give you a real credit, a share of net profits if we make money, and I’ll help you get your next gig.’

People will say yes. Not because they’re desperate. Because you treated them like adults.

Indie film isn’t about how little you spend. It’s about how wisely you spend it. And the smartest investment you can make? Your crew.

What’s the minimum I should pay a crew member on an indie film?

There’s no legal minimum for non-union indie films, but $125-$175 per day for assistants and $300-$600 for skilled roles like camera or sound is the current standard for respectful pay in the U.S. Paying less than $100/day risks burnout, resentment, and crew turnover.

Can I pay crew in equity instead of cash?

Yes-but only as a supplement, not a replacement. Equity works best for roles that are less critical to daily operations (like composers or colorists). Never use equity to avoid paying your director of photography or production manager. Cash builds trust. Equity is a bonus.

How do I handle crew who want to be paid more than my budget allows?

Be upfront. Say, ‘I wish I could pay you more. Here’s what I have.’ Then offer something else: deferred pay tied to a clear revenue goal, a producer credit, a referral to another filmmaker, or help with their own project. Sometimes, the trade-off is worth it.

Is it okay to ask crew to work for free?

No. Not if they’re doing professional work. If someone is operating a camera, recording sound, or managing the set, they’re not a volunteer. They’re a professional. Asking them to work for free devalues their skills and sets a bad precedent for the whole industry.

What if I can’t pay anyone at all?

Don’t make the film. Wait until you have enough to pay at least your core crew. A film made with unpaid labor often has poor quality, low morale, and no follow-up projects. A film made with a small, paid team can become a calling card that opens doors.

Next Steps

Before you start shooting, sit down with your key crew. Show them your budget. Ask what they need. Write it down. Sign it. Even a simple email agreement counts.

Then, pay them on time. Always.

Because in indie film, the people who show up every day-no matter how little they’re paid-are the ones who make the movie real. Don’t waste their trust.

Comments(5)