Think about the world of production design in film. It’s not just about pretty sets. It’s about making the impossible feel real-without spending millions. On a tight budget, every dollar counts. A single prop, a repainted wall, or a cleverly lit hallway can sell an entire universe. That’s the magic of smart production design.

What Production Design Really Does

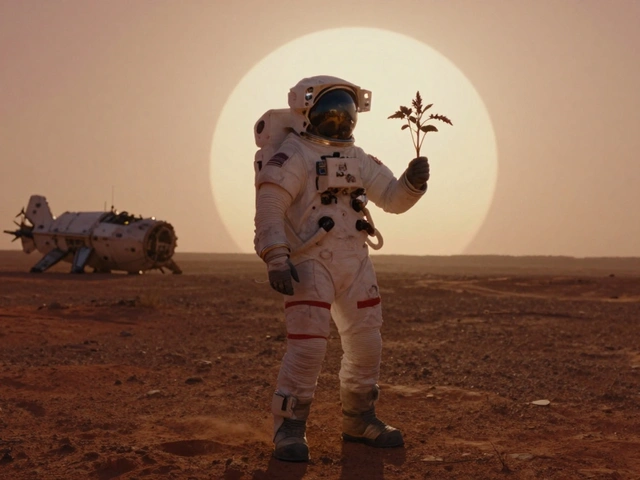

Production design is the invisible force behind every film’s atmosphere. It’s the color of the walls in a horror movie that makes you feel trapped. It’s the worn-out couch in a family drama that tells you everything about the characters’ lives. It’s the rusted spaceship in a sci-fi flick that feels like it’s been flying for 30 years.

It’s not about buying new things. It’s about seeing potential in what’s already there. A real abandoned factory isn’t just a location-it’s a character. A thrift store lamp with a cracked shade? That’s not junk. It’s history. Production designers are storytellers who work with space, light, texture, and time.

When you watch The Florida Project, the motel’s peeling paint and faded rainbow signs aren’t accidents. They were chosen because they told the story of economic struggle without a single line of dialogue. That’s production design at work.

How Low-Budget Films Build Believable Worlds

Low-budget films don’t have the luxury of building sets from scratch. They don’t have teams of carpenters, painters, and prop masters working 18-hour days. So they get creative.

Take Primer, made for under $7,000. The entire film takes place in garages, living rooms, and parking lots. But the time-travel scenes? They feel real. Why? Because the designer used real electronics-old hard drives, blinking LED lights, duct-taped wires-things you’d find in a basement workshop. No CGI. No fake props. Just real objects, arranged with purpose.

Another example: Mad Max: Fury Road started as a low-budget project. The production team didn’t buy new vehicles-they found old trucks, modified them with scrap metal, welded on spikes, and painted them with rust-colored spray paint. The result? A post-apocalyptic world that felt lived-in, dangerous, and real. No studio spent $150 million on fake sand. They just made what they had look like it had survived a war.

The rule? Use what’s there before you build what isn’t. A university theater’s old set pieces? Borrow them. A local hardware store’s leftover paint? Use it. A neighbor’s garage full of vintage furniture? Rent it for $50 a day.

Key Tools of the Trade on a Budget

Here’s what successful low-budget production designers actually use:

- Thrift stores and flea markets - These are goldmines for period-specific props. A 1980s VCR, a rotary phone, or a dusty typewriter can instantly set a time period without costing hundreds.

- Local artists and students - Film schools are full of painters, sculptors, and model-makers who need experience. Offer them credit, meals, or a small stipend. They’ll build you custom pieces you couldn’t afford otherwise.

- Repurposed materials - Cardboard, foam board, and plywood can become walls, furniture, or alien landscapes. Paint them right, and no one will know the difference.

- Lighting hacks - A single LED panel and a bedsheet can turn a bedroom into a moody noir scene. Use natural light. Shoot at golden hour. Avoid expensive studio lights.

- Color psychology - Red walls create tension. Blue tones feel cold and lonely. Yellow feels nostalgic. Pick your palette before you buy anything. Color is cheaper than construction.

One indie director in Austin turned a vacant laundromat into a 1970s underground lab by painting the walls neon green, hanging old washing machines as “equipment,” and using laundry detergent bottles as beakers. The scene looked like it cost $50,000. It cost $300.

Where to Find Free or Cheap Locations

Location is everything. And it’s often the biggest expense.

Instead of renting a studio, look for places that are already empty:

- Abandoned schools, hospitals, or factories - Many are owned by cities or nonprofits and will let you shoot for free if you promise to clean up.

- Public libraries - Quiet, well-lit, and full of character. Perfect for interiors.

- Friends’ homes - A family’s basement, attic, or backyard can become a spaceship, a haunted house, or a war bunker with the right lighting and props.

- Seasonal spaces - A Christmas tree lot in January? Turn it into a dystopian refugee camp. A deserted golf course in winter? That’s your alien planet.

Always ask for permission. But don’t assume they’ll say no. Many people love the idea of being part of a movie-even if it’s just a 10-minute scene.

How to Make a Set Feel Expensive

Here’s the secret: texture beats size.

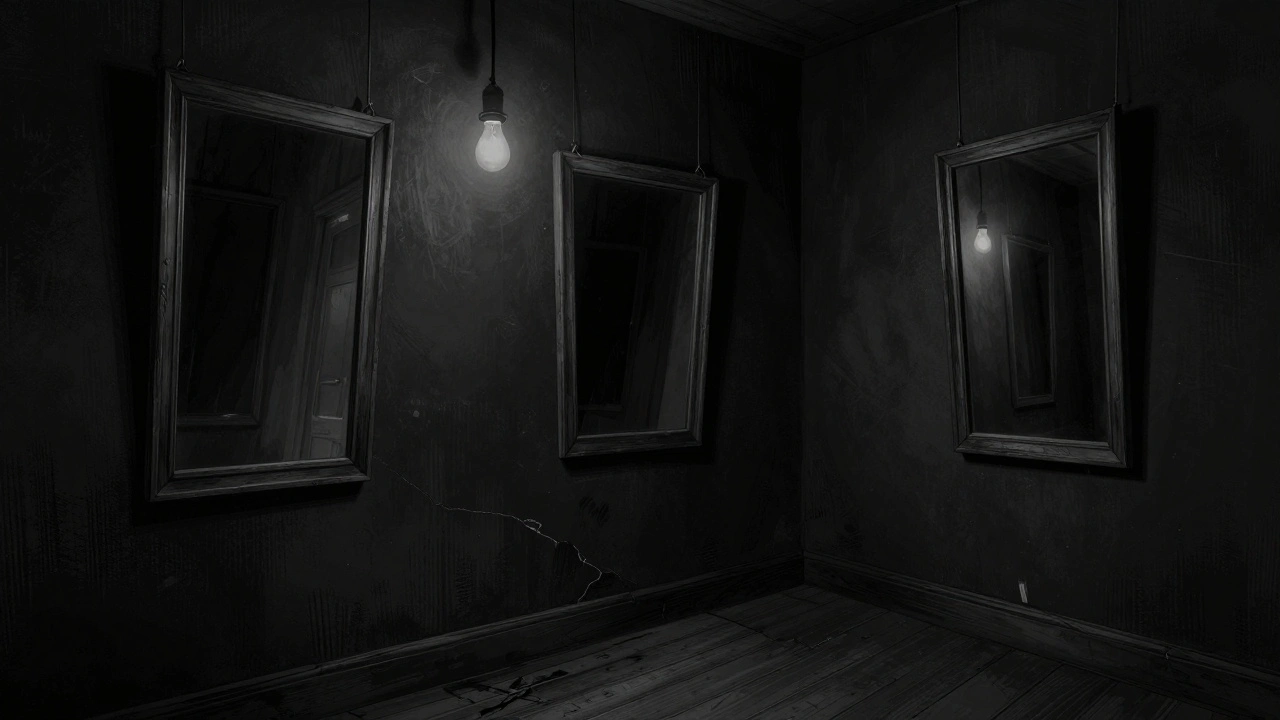

A small room with peeling wallpaper, scuffed floors, and a single flickering bulb feels more real than a giant, sterile set with perfect lighting. Why? Because real places are messy. Real people leave things out. Real walls have stains.

Use these tricks:

- Distress everything - Sand edges of furniture. Smudge walls with coffee grounds. Let dust settle naturally. Avoid shiny, new-looking surfaces.

- Layer your props - Don’t just put a chair in the corner. Put a chair, a stack of old magazines on it, a half-empty coffee cup, and a torn blanket draped over the back. Life happens in layers.

- Use real objects, not replicas - A real 1990s alarm clock with cracked plastic looks more authentic than a $200 prop replica.

- Let the environment breathe - Don’t fill every inch of frame. Leave empty space. Shadows matter. Silence matters. A bare wall can be more powerful than a cluttered one.

One production designer working on a micro-budget horror film painted a hallway with black spray paint and hung old mirrors at odd angles. The result? A corridor that felt like it was stretching into another dimension. The cost? $40 in paint and three borrowed mirrors.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Even smart designers mess up. Here’s what not to do:

- Buying too much new stuff - If you’re spending money on new furniture, you’re doing it wrong. Rent, borrow, or repurpose first.

- Ignoring sound - A creaky floor, a dripping faucet, or a buzzing fluorescent light can make a set feel alive. Record ambient sound on location. Use it in post.

- Forgetting scale - A tiny room with a giant bed looks fake. A giant room with a tiny chair feels lonely. Match the scale to the story.

- Over-lighting - Too much light kills mood. Use shadows. Let parts of the set disappear.

- Copying big-budget films - You can’t afford the same look. Don’t try. Find your own visual language.

One team spent weeks building a futuristic control room-only to realize it looked like a 1980s video game. They scrapped it, used a real server room from a local tech company, and added a few blinking LED strips. The scene became the film’s most memorable moment.

Real Examples That Changed the Game

Here are three low-budget films that nailed production design with almost no money:

- Paranormal Activity (2007) - Shot in a real house. The production designer used the family’s actual furniture, photos, and decor. The film’s realism came from authenticity, not art direction.

- Boyhood (2014) - The same house, same furniture, same wallpaper was used over 12 years. The aging of the space became part of the story.

- The Last Black Man in San Francisco (2019) - The crew restored a real house that had been abandoned for years. They didn’t build a set-they rebuilt a memory.

These films didn’t spend millions. They spent time, care, and attention to detail. That’s what production design is.

Where to Start If You’re New

If you’re a first-time filmmaker with a small budget, here’s your action plan:

- Write your story first. Know the mood, time period, and emotional tone.

- Walk around your town. Take photos of interesting buildings, rooms, and objects. Save them in a folder.

- Visit thrift stores, yard sales, and salvage yards. Take notes on what you see.

- Reach out to local art schools. Ask if students need projects.

- Find one location you can use for 90% of your scenes. Build your story around it.

- Use color as your main tool. Pick two dominant colors. Stick to them.

- Let your set breathe. Don’t fill every space. Let shadows do the work.

You don’t need a big budget to build a world. You just need to see the story in the cracks, the dust, the light, and the silence.

Can you do good production design without a dedicated designer?

Yes. Many indie filmmakers act as their own production designer. If you have a strong visual sense and can communicate your ideas clearly, you can guide your crew or volunteers to build what you need. The key is having a clear vision and knowing where to look for resources.

How much should I budget for production design on a low-budget film?

On a $50,000 film, production design should take no more than 10-15% of the budget-that’s $5,000 to $7,500. Most of that should go to paint, props, and rentals, not construction. Many teams spend under $2,000 by relying on free or borrowed items.

What’s the most important thing in production design?

Consistency. Every object, color, and texture should support the story’s mood and time period. A 1950s kitchen with a modern coffee maker breaks immersion. A spaceship with wooden floors and hand-painted signs feels more real than one with shiny metal walls.

Do I need to build sets from scratch?

No. In fact, most successful low-budget films don’t. They find real locations and modify them. A bedroom becomes a lab. A garage becomes a spaceship. A library becomes a prison. The best sets are the ones that already exist.

How do I make a modern set look like it’s from the 80s?

Change the color palette-use mustard yellow, burnt orange, and brown. Swap out modern electronics for vintage ones like CRT TVs, rotary phones, or cassette decks. Add textured wallpaper, shag carpets, or plastic furniture. Even small details like a stack of VHS tapes or a rotary phone on the wall sell the era.

Comments(5)